Sebring

Circuit Overview

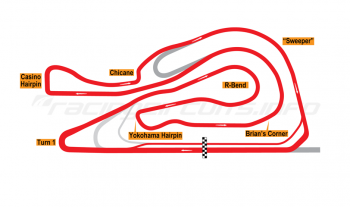

Sebring Raceway is a mecca for sportscar fans the world over, having held its famous 12 Hour race since 1952. Now supplemented by a 1000kms race for the World Endurance Championship the day before, Sebring is veritable feast for endurance racing enthusiasts.

Built on the runways and connecting roads of a former US Army Air Base, what was once a temporary affair is now a permanent facility used year-round for testing and club racing. Indeed, Sebring is now one of the oldest continuously operating circuits in the whole of the USA.

The track also hosts the Legends of Motorsport and Historic Sportscar Racing series, SCCA regional racing and is the winter home of the Skip Barber Racing School.

Circuit History

The airbase on which it stands was built at the height of World War Two, when the city of Sebring donated land for a new air training school. In June 1941, construction crews moved in and began creating the runways and barracks, with a networks of buildings, roads and sewerage systems that effectively made it a small self-contained city.

Shortly before completion, the orders came through that the base was to be expanded to become the first Combat Crew Training School in the United States for heavy bombers, requiring much more robust and enlarged runways. To withstand the pounding of the giant B-17 Flying Fortress bombers, engineers poured multiple slabs of concrete to form the runways, which criss-crossed the site in four directions. Named Hendricks Field in honour of a fallen flight instructor, the base spent the rest of the war training hundreds of pilots for B-17, B-24 and later, B-29 Superfortress flight crews.

With the end of the war, however, it soon became surplus to requirements and after a short period of inactivity, the abandoned airfield was turned over to the City of Sebring to become Sebring Air Terminal, now Sebring Regional Airport & Commerce Park.

Racing takes shape

It was in this guise that Sebring first came to the attention of the racing community. One day in 1949, sportscar racers Sam Collier and Bob Gegen were flying overhead when they spotted the airfield below and decided to take a closer look. On landing, they asked to see the person in charge and asked if it would be possible to hold a race on the grounds there. Allen Altvader, who ran the air terminal, said it would be a matter for the city council to decide but took them on a tour of the facility.

Evidently impressed by what they had seen, the pair departed to begin preparations, leaving Altvader to talk to the council members to sound them out. At the Watkins Glen road race in 1950, Collier and Gegen evidently shared their idea with other racers to sound them out; tragically, Collier was killed at that very race and it seemed that the idea might have died with him.

Enter fellow racer Alec Ulmann, who had been inspired by a trip to Le Mans and harboured ambitions to bring European style racing to the USA. The former president of the Dowty Equipment Corporation, which manufactured landing gear for military aircraft, Ulmann was also keen on starting a new business refitting war-surplus aircraft for civilian uses. On a trip to seek out a base for his adventure, he decided to check out Sebring to see for himself whether Collier and Gegen had been onto something.

In his book 'The Sebring Story', Ulmann writes that what he found seemed ideal for his vision: "Two glorious one-mile straightaways, so necessary for top speed competition, [and other roads that] could simulate Le Mans' right-angle turns of Mulsane and Arnage and the 200mph straight passes at the Hunaudières."

The early years

Convinced it could work, he ploughed in what money he could into organising the first race, held on New Year's Eve, 1950. Around 30 cars from across the country turned out to contest the Sam Collier Six Hours Memorial, run to a complicated equivalence formula which ensured that the handful of local spectators could have no clue who was winning! Rather remarkably, it was won by the team of Ralph Deshon and Fritz Koster, who had borrowed a spectator's tiny (and otherwise unsporting) Crosley Hot Shot to participate in the event.

The first course was very primitive – essentially marked out with hay bales and featuring a pit area that was little more than lashed together trestle tables – but the event had proved enough of a success to be repeated 14 months later in what would become its now traditional early season date.

In its more familiar guise as a 12 hour endurance race, the revised course used a different combination of the former army base's roads alongside the North/South and East/West runways. This was to become the classic Sebring layout and was a true test of endurance. The bumpy concrete sections took their tolls on the cars, while the night time running on the maze of roads often played tricks on the drivers – many would become disoriented and lose time navigating their way back onto the proper course.

In 1959, Ulmann pulled off something of a coup, organising the first US Grand Prix for Formula One machinery. In the end, the bumpy concrete proved a poor match for the sophisticated single seaters and the event failed to cover its own costs – indeed, Charles Moran and Briggs Cunningham stepped up to pay the prize monies out of their own pockets when the promoter's cheques bounced. After a further one-off race at Riverside, F1 found a happier home at Watkins Glen.

Sebring's darkest hour

By 1966, the 12 Hours was well-established and became another battleground between Ford and Ferrari, in preparation for Le Mans. That year's race was to prove Sebring's grimmest hour, however, thanks to a string of fatalities which exposed the inadequacy of safety facilities. First Canadian Bob McLean was killed when his Ford GT40 suffered mechanical trouble sending it careering into a telegraph pole, whereupon it burst into flames with the hapless McLean trapped inside. Further tragedy was to strike with two hours to go, when Mario Andretti's Ferrari slowed with gearbox trouble, only to be clipped by Don Wester's Porsche, sending Wester first into a group of spectators who were stood in a restricted zone and then into the side of a warehouse. Four spectators, including a nine-year-old boy, were killed and Wester suffered multiple injuries.

Ulmann and the organisers came under fierce criticism in the aftermath, with threats of lawsuits and potential boycotts mooted. Serious plans soon emerged to move the race to the then-new Palm Beach International Raceway. The track's owner, Pete McMahon, was willing to invest $1.5 million in track upgrades that would include extending its length from 2 miles to 5.5 miles. In addition 80 covered pits would be built for the entrants plus bleachers for the spectators, private parking, a scenic lake and spectator access roads. A 10 year deal was duly signed to host the renamed Florida International Grand Prix of Endurance.

Mother Nature had other ideas, however. The Palm Beach area suffered through two months of unprecedented rains, delaying the start of any construction work. Finally in November, Palm Beach officials announced they were abandoning the 10-year contract to hold the race because the rains and high water table prevented them from getting the track ready in time.

Resurrection

Hurriedly, Sebring had to be readied for racing once again. Concessions to safety were made, including the moving of the warehouse straight onto a parallel road to keep the cars further away from buildings. They then eliminated the old Webster corner and replaced it with the Green Park Chicane, while nylon belting that was designed to catch Navy planes that might overshoot a carrier landing or a short runway was installed along the new Warehouse Straight. The track's insurers also insisted spectators must be kept at least 120 feet from the track rather than the previous 75 feet, while chain link fencing and Armco barriers were also introduced.

Despite the upgrades, Sebring was still a primitive place, with few of the amenities to be found at permanent venues. This didn't seem to put off the crowds, who would pile into Green Park to camp, party and watch the race, sometimes almost as an afterthought. The atmosphere was fairly wild and in many cases not for the faint-of-heart.

Into the modern era

There were no further significant track changes until 1983, when the first of several course changes marked a push to reduce the circuit's impact on the operations of the airport, which was seeing increasing flight traffic. This would ultimately see the portions using the the North/South runway reduced and finally eliminated. In tandem came a general upgrade of paddock facilities, which saw the relocation of the backstretch in 1984 – now named the Ulmann straight – to create more room.

Bigger changes came in 1987, when new sections were built from Turn One to Turn Three, eliminating much of the concrete apron, and the track was rerouted away from the North/South runway altogether through a new stretch of permanent road which rejoined onto the Ulmann Straight. Further revisions in 1991, 1996 and 1998 would ultimately mean the circuit would become a permanent venue, separate from both the airport and adjoining business park, allowing the track to operate independently and without interruption.

The track underwent ownership changes in the 1990s. Firstly it was acquired by Scandia Racing boss Andy Evans, who subsequently sold it to Don Panoz in 1997. Under Panoz's stewardship, there has been further investment, which has seen the construction of the Château Elan Hotel overlooking the hairpin and the creation of separate club and school courses.

In September 2012 the Panoz Motorsport Group was sold to NASCAR, which thus became the new owner of Sebring Raceway. The famous 12 Hours continues, now part of the NASCAR-sanctioned United SportsCar Championship, while the track also hosts the Legends of Motorsport and Historic Sportscar Racing series, and is the winter home of the Skip Barber Racing School. Many teams also continue to use Sebring for winter testing due to the warm climate.

The introduction of the FIA WEC 1000 Miles of Sebring for 2019 brought the need for a second paddock to be constructed with its own separate pitlane along the Ulmann Straight. The start and finish remained in its traditional place, however.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

- Sebring International Raceway, 113 Midway Drive, Sebring, Florida 33870, USA

- +1 863 655-1442

- Email the circuit

- Official website

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 5286

Plan a visit

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.