Roosevelt Raceway

Circuit Overview

Built in the 1930s to host the revived Vanderbilt Cup races, Roosevelt Raceway at Westbury, New York, was a brave attempt to generate new interest in road racing in the USA and was the first permanent closed course of its kind in the country.

After briefly capturing the world's attention, the circuit collapsed into financial ruin when the promoters over-reached themselves and was redeveloped as a harness racing track.

A street race around the internal roads and parking lots of the harness track hosted a one-off sportscar race organised by the SCCA in 1960, after which the racing engines fell silent.

Circuit History

To understand the significance of the Roosevelt Raceway, you have to skip back a generation to the very earliest days of motorsport. William K. Vanderbilt Jr, heir to a vast transportation fortune, was a motorsport enthusiast and New York resident. His dream was to encourage the faster development of the automobile industry in the USA through competition with its European counterparts. In 1904, he launched the Vanderbilt Cup to provide the platform and organised a 300-mile race on public roads across Long Island.

The idea proved a hit, though the dangers of racing on public roads which were ill-designed for the purpose soon became apparent, with crowd control problems an issue from the beginning. After a spectator, Curt Gruner, was killed in 1906, the race was cancelled for the following year while a new solution was found.

Vanderbilt formed a company to build the Long Island Motor Parkway, one of the country's first modern paved parkways that could not only be used for the race but would open up Long Island for easy access and economic development. Construction began in 1907 of the multimillion-dollar toll highway, to run from the Kissena Corridor in Queens County over numerous bridges and overpasses to Lake Ronkonkoma, a distance of 48 miles (77 km).

In 1908 the race was back on, using parts of the new highway. To the delight of the large crowd, 23-year-old George Robertson from Garden City, New York became the first American to win the event driving the American Locomobile. The Vanderbilt Cup would continue on Long Island until 1911, when it headed off to a variety of venues in Georgia, Wisconsin and California before the USA's entry into the First World War precipitated the cancellation of the 1917 race.

Enter the flying ace and another generation of Vanderbilt

The American economy had taken a battering during the Great Depression of the 1920s but as prosperity began to return in the 1930s, a new generation began work to revive the art of road racing. Unlike in Europe where it was the pre-eminent form of motorsport, in the USA road racing had all but fallen away, in favour of dirt tracks and board-track oval racing. However, as the economic recovery continued, World War One ace pilot and accomplished racer Eddie Rickenbacker began assembling a group of people to reverse that trend, planning a new race to allow the American drivers and cars the chance to battle with the best Europe had to offer.

Joining Rickenbacker in the venture were Boston Redskins owner George Preston Marshall, 1908 Vanderbilt Cup winner George Robertson and George Washington Vanderbilt III, nephew of 'Willie K', who offered to sponsor a 400-mile race under a revived Vanderbilt Cup banner.

In February 1936 the group announced the creation of a new circuit to host the race, located at Roosevelt Field, the airfield at Westbury, around 30 miles from the centre of New York. This was the departure location for Charles Lindburg's famous solo transatlantic flight less than a decade before.

To design the course, they enlisted Mark Linenthal, an architect and friend of Marshall and Art Pillsbury, who was involved in the construction of most of the nation's steeply banked board tracks. It was to be a lavish facility in order to attract the east coast social set, rather than the typical working-class racegoers from the dirt tracks. A huge double-deck grandstand overlooked the main straight, while there was also a posh clubhouse, well-equipped indoor garages and ample parking.

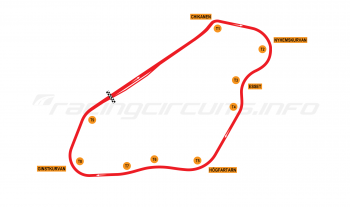

The track design was less successful. Aside from the main long straight, it was a rather tortuous affair, with numerous switchbacks and slow-speed corners in a flat layout which was designed in such a way that all parts would be visible for the grandstands, which would cater for up to 50,000 spectators. It would not look terribly out of place in modern times; the Ricardo Tormo Circuit in Valencia employs a similar layout today.

Unfortunately, this track design would prove ill-suited in particular to the American racers of the day, which often boasted one or two gears due to their oval racing background, while even the imported European stars found it difficult. It was also bumpy, with a surface composed of sand, clay, asphalt and tar.

There was nothing wrong with the prize money, however, with a total purse of $60,000 providing quite the payday for the top finishers. Unsurprisingly and in the grand traditions of the Vanderbilt Cup races of old, this meant a good turnout of European entries. Twelve of the 45 drivers that started the race were Europeans driving an English ERA or an Italian Alfa Romeo, Bugatti or Maserati cars. Indeed, the works Ferrari team sent its Alfa Romeos for Tazio Nuvolari, Antonio Brivio, and Nino Farina.

Nuvolari was in unbeatable form, missing out on the front row when his transmission failed on pole day and having to make do with setting his time on the second day, with a run of just under 70mph that no-one else could match. Teammate and protégé, Nino Farina, was fifteen seconds behind and struggling to adapt to the loose surface. Practice and qualifying had shown that even the European stars were unable to meet the predicted lap speeds (wags in the local media joked that commuters travelled faster on the Long Island Motor Parkway), so it was decided to cut the race distance to 300 miles to prevent the event dragging on long into the evening.

On race day Nuvolari would start down in 8th place but made his way to the front in very short order and was never headed thereafter, leading all of the 75 laps and romping home the winner like a man possessed, despite dropping a cylinder early on. Jean-Pierre Wimille trailed home in second more than eight minutes and two laps behind, with Brivio another lap down. 'Wild' Bill Cummings was the first American to cross the line in seventh, a rather embarrassing twenty-five minutes behind.

Race organisers announced a crowd of 60,000 had turned out, but few believed that figure and photographs confirm the grandstands were far from full. Part of the problem was the pricing of tickets, which proved effective at keeping the 'riff-raff' out but also dissuaded plenty of the well-heeled too. The New York papers panned the event but the organisers ploughed on, determined to make it a success. Several of the American drivers, no doubt with an eye to the future prize money, did deals to buy European cars in anticipation of greater things to come.

Course revisions to boost speeds

If anything, Rickenbacker and co upped the ante further for 1937, offering an increased prize purse of $70,000 dollars, with awards for lap leaders and the leading American car. It was clear to all however, that changes to the track would need to be made to pep up the show.

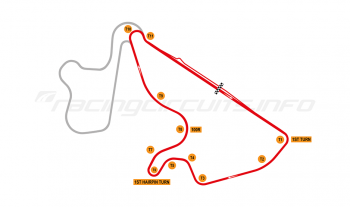

In order to up the average speed, the twistier sections in the centre were eliminated and banking added at the final turn. Reports vary as to the actual amount of banking, but something in the region of 18-23 degrees looks about right from contemporary footage. The effect was to launch the cars down the main straight and into a first corner which had been eased to create a constant radius turn.

Another big improvement was the road surface. While not asphalted in the way we would understand today, it was treated to a new rock and asphalt mixture, leaving a surface that was essentially a stone road with an asphaltic binder. This greatly aided the grip and removed the loose surface tendencies of the original course, though judging by race footage, it remained as bumpy as ever and there was grumbling from the European drivers in particular about the difficulty of finding braking points on the reconfigured course.

All of the changes - and the increased prize purse - persuaded some of the top European manufacturers to enter the 1937 race. The German Auto-Union and Mercedes-Benz teams plus the Scuderia Ferrari Alfa Romeos were fully represented, entering two cars each. American driver Raymond Mays was also in an Alfa, having bought the spare car from the 1936 race and fitted a larger supercharger. To the evident disgust of the works Ferrari team, the modified Mays car was quicker...

The race itself had been scheduled for Saturday July 3, having been brought forward in the season and to allow for contingencies in case of a race delay to allow the European teams time to ship their cars back home. This proved wise, as rain began falling heavily at the scheduled start time and the organisers were forced to postpone the race by 48 hours to the Monday, as racing was not permitted on Sundays.

The race finally got underway, with a message relayed by wire from President Franklin Roosevelt at his Hyde Park residence. Bernd Rosemeyer was the early leader for Auto-Union but was passed by the Mercedes of Rudolf Caracciola, who opened up a 6 second gap. Rosemeyer fought back and the pair battled hard until lap 22, when Caracciola's engine failed. By this stage, the Alfa of Nuvolari was also out, its engine having thrown a rod in protest at the exuberant way its driver was having to throw it round the course in order to keep up. Nuvolari switched to Farina's car, only to suffer further engine maladies on lap 50. He handed the car back to Farina, who remarkably was able to limp the car home in fifth.

Up front there was now no stopping Rosemeyer, with the second Mercedes-Benz of Richard Seaman coming home as runner up, almost a minute behind. The American cause was upheld by Mays, who managed a podium finish in his Alfa, ahead of the second Auto-Union of Ernst von Delius. First American car home was again 'Wild' Bill Cummings in seventh in his Miller-Offenhauser.

Once again the organisers declared the event a sell-out, stating 70,000 had turned out to watch. As with the previous year, this figure was highly dubious. A second race had been planned for Columbus Day (the date of the 1936 race) but this was soon pulled, so the final race of the year on the track was the ARCA Grand Prix and Coupe de Sport on September 25.

As fate would have it, this was the final road race on the circuit, as in early 1938 the company formed by Rickenbakker and his associates collapsed into bankruptcy, which rather reinforced that the spectator figures were way short of their stated numbers and certainly not enough to recoup the enormous costs of construction. Losses of a staggering $1 million were reported.

Midget racing to the rescue

There still seemed to be a future for the venue, however. In May a Los Angeles amusement park owner called Frank C. Hulbert announced that he had secured a ten-year lease on the track and would be promoting a 300-mile stock car race there on Labor Day. Despite this, nothing came of the plans and it wasn't until July 1938 that the track would re-open, to some irony given the intention of its original founders, as a venue for midget racing. A small oval was created in front of the main grandstand by joining a small portion of the main straight and the parallel section of the adjacent straight with two sharp 180 degree turns.

Racing resumed, though the tight nature of the corners meant that average speeds often failed to top 50mph. It proved a short-winded affair, as a betting scandal soon enveloped proceedings, with accusations that some of the drivers were fixing the races, while there was also a reported fatality. By August, it was all over and the racing ceased once again.

It was not the end of the oval racing story however, as a further attempt was made in June 1939, when an event was staged for the crowds attending the Westchester Cup polo matches at nearby Meadow Brook. It evidently failed to find much favour, with the press scornfully dismissing the course as a "two-bit parking lot".

However, the oval was extended to 1.5 miles later that year, in anticipation of hosting the national midget racing championships.in August. This allowed more of the grandstands to be used and drew a big crowd; reports suggest crowds of between 55,000 and 63,000 spectators turned out, easily making it the best-attended event the Raceway had ever held. Even this success however, could not prolong motorsport's tenure on the site. In early 1940, the site was sold and redeveloped as a harness racing track, featuring a more traditional type of horse power.

Final hurrah with yet another Vanderbilt

This wasn't quite the final chapter in the Roosevelt Raceway motorsport history, however. In 1960, Cornelius Vanderbilt, nephew of Willie K, leant his backing to reviving the Vanderbilt Cup once again, this time as race organised by the SCCA's New York region. The event was to be staged in the grounds of the Roosevelt Raceway harness track, using existing internal roads and the parking lot.

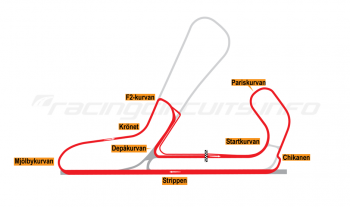

A 1.5 mile course was created, featuring a main straight of almost half a mile. In response to the prestige of the trophy on offer, the SCCA decided to allow professional racers to take part in the main race, though the nine race undercard remained firmly for amateurs.

The Cornelius Vanderbilt Cup Race was run on Sunday, June 19, 1960, using the newly popular Formula Junior category. Some famous names were persuaded to take part, among them Jim Rathmann, the reigning Indianapolis 500 champion and Rodger Ward who had won the same race in 1959. Several future Formula One drivers also took part, including the Rodriguez brothers, Pedro and Ricardo and Lorenzo Bandini, while sports car stars Jim Hall, Carroll Shelby and Walt Hansgen were also in the field.

By SCCA regional racing standards, an excellent crowd of more than 37,000 people attended the race, though it proved a pale imitation of the Vanderbilt Cup races of old. At just 75 miles in length it was little more than a sprint race, though it still proved something of a challenge for the under-developed formula cars. Only 14 of the 33 starters managed to complete the 50 lap race and of the big names only Pedro Rodriguez was among them, coming home fifth. His pit crew unsuccessfully argued that timing and scoring had erroneously missed out one of the Mexican's laps, which would have promoted him to the win. Instead, it was Henry Carter, of Litchfield, Connecticut, a 37 year old salesman and national amateur road racing champion, who took the spoils in a Stanguellini Formula Junior, at an average speed of 74.95 miles per hour.

Cornelius Vanderbilt was on hand to award the trophy but any hopes that this would spark a revival in racing at the venue proved forlorn. The new Bridgehampton track had sprung up in the meantime, and the Vanderbilt Cup moved the 60 miles further east with it.

Circuit info

This is a historic circuit which is no longer in operation.

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 825

Location Information

Roosevelt Raceway was located at Westbury on Long Island, New York. Today, the inevitable surge of development means that there is almost nothing to suggest the likes of Nuvolari, Carracciola and Rosemeyer ever competed here. Even the harness racing track is gone and the whole area has been redeveloped. Only the Roosevelt Raceway name lives on, somewhat incongruously, as the title of the shopping centre which now occupies the site.

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.