Detroit

Circuit Overview

The streets of the motor town are no stranger to hosting racing, with both Formula One and Indycar having hosted events in the area around the Renaissance Centre in the 1980s.

Now Indycar is returning, abandoning nearby Belle Isle for a new course laid out around the downtown streets, in a bid to bring racing to a wider audience.

The new Detroit Grand Prix course features almost none of the roads of the original and, it is to be hoped, proves less of an attrition-fest than its earlier incarnation.

Circuit History

Head back into the early 1980s and Detroit and the State of Michigan were emerging from difficult financial times. The auto industry on which it depended had undergone a turbulent 1970s, with the downturn caused by the oil crisis and increased competition from foreign imports leaving the big three domestic motor makers in trouble. Add in the effects of a recession causing unemployment to skyrocket and suddenly the city seemed in a downward spiral.

To combat this, some of the most influential business leaders in the city - headed by Henry Ford II, investor and philanthropist Max Fisher and banker Robert Surdam - formed Renaissance Inc, a nonprofit corporation with the goal of directly addressing the city’s economic and social problems and ushering in a new era of vitality.

Among the group’s successes was the construction of the giant Renaissance Center skyscraper complex, housing offices, retails spaces and a large hotel at its core. This opened in 1977 and was a bold statement in an effort to turn around the downtown areas slightly down-at-heel feel.

To further the comeback, the city fathers wanted an international showcase event to help showcase Detroit to the world and boost its somewhat fading reputation. Long Beach had used its Formula One race to great effect and so it was understandable that Detroit would look to do the same. With Formula One looking to expand its calendar under impresario Bernie Ecclestone, it seemed a match made in heaven.

So it was that a deal was done for the Detroit Grand Prix to be included on the 1982 Formula One World Championship calendar, becoming the third US event that year, after events at Long Beach and Las Vegas. As with the Caesar’s Palace circuit, the Detroit event was excused of the usual requirement to host another race to test facilities prior to the Grand Prix.

The first course emerges

It was perhaps understandable that the investors wanted the gleaming towers of the Renaissance Center as the backdrop to the race, though that did present some logistical problems for the course designers. Closing down large sections of usually busy city streets while concrete barriers and catch fencing were installed was not designed to make the race universally popular with locals. Add in the fact that the track had to cross over tram tracks and the difficulties spiralled.

There were however practical benefits to the location for the race organisers; the Renaissance Center hotel could be utilised by the teams and sponsors, while the media centre could also be housed there, with good views down over the first part of the circuit.

The course also took in the Detroit Convention Center at one end, which was used to house the paddock space for all of the Formula One and support teams, there being little room behind the temporary course’s pit lane. Inside the building’s glass foyer well-heeled race fans could enjoy watching the race pass by outside and on large monitors while enjoying a drinks and meals. Perhaps it was here that the idea of the Formula One Paddock Club first took off…

Less glamorous was the start/finish area and pits, which were laid out on a parking lot overlooking the Detroit River. Surrounded by grandstands, there was little room for the teams to actually work, hence why the main paddock was elsewhere - somewhat inconvenient for the mechanics but not especially unusual for a street circuit.

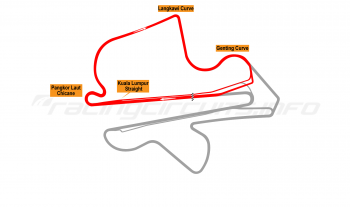

A lap of the F1 course

From the start line, the course headed through a 180 degree first corner, which tightened slightly as it exited onto Atwater Street, through a tight 90 degree right onto a short uphill stretch of St. Antoine, before turning onto Jefferson Avenue through another 90 degree corner.

A short sweeping section past a church then led to the first iteration of the circuit’s most controversial feature; a tight hairpin that was supposedly modelled after Monaco’s famous Loewe’s Hairpin, but was even tighter and with considerably less glamour. Drivers were almost universal in their dislike of this section - and it was swiftly reconfigured for the following year’s race.

After a further couple of 90 degree corners onto and off Chrysler Service Road, the course entered a sweeping section on Congress Street before a short straight . From there the track went through successive right then left 90 degree bends followed by short straights (including one which passed under a building on Larned Street) before arriving at the Western end of the circuit on Jefferson.

Here the track turned back on itself briefly in front of the Convention Center, passing over the tram tracks and heading downhill through a ramp to a parking area and under a bridge, then onto Civic Centre Drive. This curving section exited onto Atwater once again, from where the drivers would dive into the tunnel underneath the memorial gardens. Similar to Monaco, the tunnel featured a distinct curve which meant drivers were plunged into total darkness for a few seconds while still remaining flat out.

Shortly after exiting the tunnel the cars went through a medium speed S-bend onto the new section of road created for the Grand Prix. A rather clumsy tire-lined chicane adjacent to the pit entry slowed speeds onto the start/finish straight to complete the lap.

It was perhaps not the finest layout ever conceived and was not universally popular - Alain Prost and Nelson Piquet in particular were said to detest it. There wasn’t total condemnation though and some even praised its rougher edges. Veteran Motor Sport writer Denis Jenkinson said it was probably “too real” for some, adding: “Wild and woolly street racing with bumps, surface changes, tarmac, concrete, manhole covers, solid walls and a tunnel, what more could you want?”

A hesitant start

When the Formula One teams arrived (minus Toleman, whose transporter was late back from Monaco and thus elected to withdraw from the event) the circuit was palpably not ready, despite the friendly welcome given to all from the organisers.

The initial plan was for a Thursday test session to allow the drivers to familiarise themselves with the track and the officials to familiarise themselves with Formula One racing in general. But when FISA officials inspected the track, a variety of problems emerged; escape roads were inadequate and barriers were not placed to everyone’s satisfaction. The test session was quickly nixed and work began to remedy the defects.

Friday morning’s practice session also came and went as work continued, with the drivers asking for more tyre bundles at key points. In the end, the first wheels turned for an hour of practice at 4pm. This proved stop start with several red flags, including one that saw Jan Lammers briefly hospitalised for a broken thumb.

The official course length was initially stated as 2.45 miles / 3.95 km but after this first running the teams cast doubt on this number. Renault engineers began using 4.17 km/2.59 miles for their fuel calculation and a report from BMW said a similar picture. Agreement was finally reached that the track was indeed 2.59 miles long.

The various delays meant that Saturday’s schedule was heavily revised to incorporate two one-hour qualifying sessions. There were still further delays are more track modifications were made.

There was plenty of drama in the qualifying sessions, with Nelson Piquet hitting mechanical trouble in the first session and the spare car failing to get up to speed with electrical gremlins, leaving him bottom of the timing sheet, 28th overall. When rain came during the second session, Piquet was unable to improve his position and failed to qualify, leaving the reigning World Champion a frustrated spectator on Sunday.

Race day dawned with clear skies, however (which probably did little to cheer Piquet, Brabham or an embarrassed BMW). At the start, Prost blasted away in his Renault, but there were several bumps and scrapes behind him, accounting for three drivers in the first two laps. Several others retired with mechanical gremlins, before the red flag was shown on lap six after a sizeable shunt at the first turn accounted for two more.

After an hour’s delay (during which the teams ignored the rules and patched up any damage) the remaining 18 cars took the restart.

In one of his classic ‘burn from the stern’ races, John Watson charged his way through from an initial lowly grid spot of 17th, taking the win ahead of Eddie Cheever’s Talbot-Ligier, the result marking the American driver’s best ever in Formula One.

In a race of high attrition, there were only 12 finishers, of which only five were on the lead lap. It wasn’t perhaps a classic race, but it certainly was dramatic.

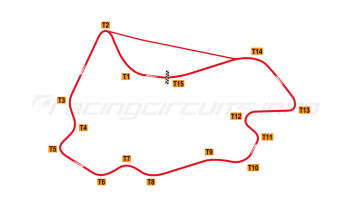

Circuit changes for 1983

Despite the somewhat lackadaisical organisation of the first race, Formula One was back in 1983. This time, things went much more smoothly, though the circuit was just as bumpy as ever, despite efforts to improve the situation.

There was some circuit changes however; gone was the hated and contrived hairpin on Jefferson Street, bypassed by a fast corner meaning the cars made multiple apexes on the way to the tight 90 degree corner onto Congress Street.

The first corner complex was also mildly revised with a slightly tighter alignment that created more run off. Ironically, it would never be required in any of the subsequent races, as drivers proved better behaved!

Several of the streets had also been resurfaced and much work was done to smooth the area over the tram tracks. The pit entry was also revised, being extended to the outside of the first part of the chicane, rather than on its exit.

Aside from further resurfacing works at various places in subsequent years, the track was largely unchanged for the remaining Formula One races. The alterations meant the track was now measured at 2.500 miles / 4.023 km.

The 1983 race would chalk up two notable final wins when Michele Alboreto took the chequered flag; it was the last time a Tyrrell would come first and also the last time a normally aspirated Ford Cosworth DFV-based engine would take victory.

Ayrton Senna would go onto prove something of a master at Detroit, winning the race for three years straight from 1986-88.

Hot temperatures and a punishing anti-clockwise course meant that the circuit was never among the driver’s favourites, so when the track broke up badly in the 1988 event the drivers became even more vocal (Senna likened grip levels to being similar to driving in heavy rain).

After the race, FISA ruled that the facilities in the temporary pits were no longer up to Formula One standards, so the organisers proposed a move to a new course on Belle Isle. This was however also deemed unacceptable and Formula’s relationship with the Motor City came to an end.

Indycar picks up the mantel

Race organisers were soon able to strike a deal to bring the more familiar (at least to US eyes) Indycar competitors to the streets, so from 1989, the Detroit Grand Prix was held for the CART series.

The unpopular chicane was eliminated for the CART races, though aside from a few vary minor radius changes to some corners, the course otherwise remained identical to that used previously by F1.

Emerson Fittipaldi won the 1989 and 1991 races for Team Penske, with Michael Andretti taking the 1990 win, having been on pole position for all three races.

The spiralling costs of hosting the race on the downtown city streets alongside growing discontent with the disruption it caused saw the Belle Isle idea re-tabled for 1992; unlike F1, CART grasped the nettle and made the switch of venue a success.

The Detroit Grant Prix would become well established on the island over the next 30 years, running until 2001 under CART rules, then as an Indycar and American Le Mans/IMSA race double header in 2007/08 and from 2012-19 and 2021/22.

Return to the streets

Despite making a good home on Belle Isle, race organisers (now headed by Roger Penske) began to explore new options to return the race the downtown area.

It followed the success of the Music City Grand Prix in Nashville, another street race in the downtown area which had proved popular with race goers.

With Roger Penske keen to provide a further re-invigoration of Detroit as it continues its recovery from the devastating effects of the 2008 financial crisis, city officials were receptive to the change in location, albeit on a much shorter course than the Formula One circuit of old.

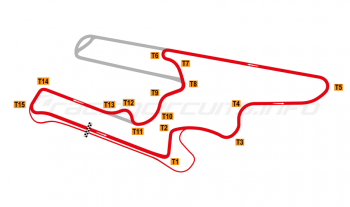

From 2023, it was announced that the Detroit Grand Prix would return to the shadow of the Renaissance Center (now the world headquarters of General Motors), with a 1.7-mile, 9-turn course encircling the complex.

The circuit’s design has been deliberately created to minimise disruption to nearby vehicle and pedestrian traffic, with local businesses consulted throughout the process. Only a few very short sections of St Antoine, Jefferson Avenue and Atwater Street are common to the old street course, with a faster overall speed expected.

An unusual feature is the pit lane configuration, which features pit boxes on either side of a central running lane, constructed within a parking lot between Franklin Street and Atwater Street. The paddock area is separate, located roughly in the same area as the old F1 start and Turn 1 complex.

Races start halfway along the back straight, which is an uninterrupted blast along Jefferson Avenue. A major overtaking point has been created at Turn 3, which is also another prominent viewing area surrounded by grandstands.

Around half the track is open for free spectator viewing, with hospitality suites and grandstands overlooking the pits and finish line.

The first race back on the streets in June 2023 proved a thrilling affair. True, like its predecessor, the track retained its old bumpy feel and there were several yellow flags as drivers got caught out by the concrete walls. Unlike the Grand Prix of old, however, there was a thrilling dice for the lead and the remaining podium positions, with drivers swapping places right up the final lap. Chip Ganassi Racing driver Alex Palou ran out the winner.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

- Chevrolet Detroit Grand Prix presented by Lear, 300 Renaissance Center, Suite 2311, Detroit, MI 48243, USA

- +1 313 748 1800

- Email the circuit

- Official website

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 375

Plan a visit

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.