Charlotte Motor Speedway

Circuit Overview

Charlotte Motor Speedway was built to provide a Daytona-style home for NASCAR racing in North Carolina. By any standard, it has succeeded, becoming a fixture on the calendar since 1960.

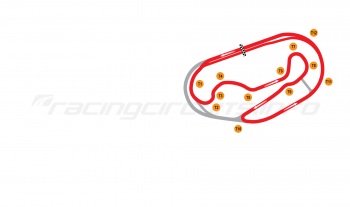

Over the years the complex has expanded beyond the main 1.5 miles quad oval to incorporate a 0.25 miles flat oval, 2.28 miles 'Roval' road course, drag strip and dirt course.

Today, the circuit continues to host 600 mile and 400 km NASCAR rounds (with on one the Roval) and events on the Nationwide and Truck Series calendars, alongside other stock car events as well as regular auto fairs, training days and test sessions. All in all, it hosts around 380 events a year, making it one of the busiest sporting venues in the world.

Circuit History

Back in the late 1950s, Curtis Turner set his sights on building an oval in North Carolina, in a bid to capitalise on the burgeoning stock car movement. The Virginian had made his money in the lumber industry before becoming one of the first drivers on the NASCAR circuit. A visit to the new Daytona International Speedway in the spring of 1959 only served to whet Turner's appetite for circuit ownership.

He had land around 10 miles north of Charlotte, at Concord in Cabarrus County and reckoned on needing to borrow around $700,000 to build a 1.5-mile superspeedway, featuring 24 degree banking in the turns. On making tentative enquiries, he learned that he was not the only person to have had the idea for a circuit in the local area; Bruton Smith, the promoter at Concord Motor Speedway and the Charlotte Fairgrounds, had hatched similar plans for a site near Pineville.

Troubled Beginnings

The pair made contact and quickly struck a deal to work together to fulfil their ambitions, negotiating with NASCAR to run a 600-mile event on Memorial weekend, aimed at rivalling the Indy 500. The race was on to complete the facility in time for the first race the following year.

Construction duly began in 1959, though it was to prove to be a troublesome build. Contractors soon found that the area under Turns One and Two and much of the planned infield was a solid slab of granite; $700,000 was spent on dynamite alone to clear it. Turner's original budget was in tatters and by the end the facility was estimated to have cost nearer $2 million. Bank loans were sought wherever they could be found as the project consumed money at an alarming rate; even the Champion Spark Plug Company was successfully tapped up for funding.

The weather gods were not on the construction crews' side either; a snow storm delayed the pouring of concrete and in the spring of 1960, Turner begged for a six-week postponement for the race. A new date of June 19, 1960 was duly pencilled in for the inaugural World 600.

By now the financial burden was beginning to take its toll and several of the contractors were becoming more than a little anxious about payment. With the race day looming, a small portion of the backstretch remained unpaved and the unhappy contractor lined up his equipment in a blockade demanding payment. It took Turner's persuasive skills (aided by Messrs Smith and Wesson) to impress upon the hapless paving engineer that this was not a way for friends to behave. The circuit was duly completed with days to spare...

Despite its difficult birth, Charlotte Motor Speedway opened for business as planned, Joe Lee Johnson completing the 400 laps to win the World 600 at an average speed of 107.735 mph. Despite three major races in its first year, the costs of construction hung heavily over the track and the repayments of the debts could not come quickly enough for the board of directors, who ousted Curtis from control of his own race track.

The writing was on the wall for the original ownership and management of the circuit – ticket sales alone were not enough to repay the debts quickly and the circuit filed for Chapter 10 Bankruptcy in December 1961. Judge J.B. Craven of US District Court for Western North Carolina appointed Robert "Red" Robinson as the track's trustee until March 1962. At that point a committee of major stockholders in the speedway was assembled, headed by A.C. Goines and furniture store owner Richard Howard. Bruton Smith departed the speedway to pursue other businesses interests.

Goines, Howard, and Robinson worked to secure loans and other monies to keep the speedway afloat and by April 1963 $750,000 had been paid to 20 secured creditors. The track emerged from bankruptcy; Judge Craven appointed Goines as speedway president and Howard as assistant general manager of the speedway, handling its day-to-day operations. By 1964 Howard become the track's general manager, and on June 1, 1967, the speedway's mortgage was paid in full. In an act of celebration of the end of this tumultuous period a public burning of the mortgage was held at the speedway two weeks later.

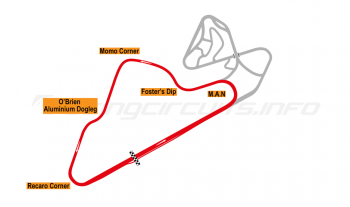

The first major investment in the circuit itself came in 1971, when a road course was added to the infield. In combination with the banked turns of the oval, this created a 2.250 miles course, used for SCCA and IMSA sportscar competitions in the years following. The oval circuit itself was resurfaced in 1973, its original surface have reached the end of its life expectancy.

Smith Returns

By the mid-1970s, Bruton Smith had amassed a small fortune from his Illinois car dealerships and began buying back shares in the facility he had helped to build. By 1975 Smith had again become the majority stockholder in the speedway and installed Howard "Humpy" Wheeler as general manager. Richard Howard quit as president and track manager early the next year, complaining that the speedway was effectively being run from Illinois.

Wheeler and Smith began an ambitious expansion plan that saw Charlotte become one of the biggest and best-appointed sports stadia in the country. New grandstands and luxury suites were added along with modernized concessions and restrooms, while 1984, saw a unique addition; 40 condominiums were built overlooking turn one. Charlotte thus became the only sports facility in America to offer year-round living accommodation. Twelve additional condominium units were added in 1991.

By 1988 Smith Tower, a 135,000-square-foot, seven-story facility, had sprung up housing the speedway's corporate offices, ticket office, gift shop, leased office space and The Speedway Club, an exclusive dining and entertainment facility. A quarter-mile oval was added to the front stretch the same year, used by Legends race cars.

In 1992, Smith and Wheeler directed the installation of a $1.7 million, 1,200-fixture permanent lighting system around the track developed by Musco lighting. The track became the first modern superspeedway to host night racing and was the largest lit sports arena until similar illuminations were added to Daytona International Speedway in 1998. Elsewhere, competitors benefited from a new $1 million, 20,000-square-foot garage area in 1994.

Name change

In 1999 the circuit signed a naming-rights deal with Lowe's Home Improvement Stores to become the Lowe's Motor Speedway. Lowe's chose not to renew its naming rights after the expiry of the 10 year deal and the circuit reverted to its original name in 2010.

At its height, the circuit could accommodate more than 170,000 spectators, though recent years have seen a reduction in seating capacity, the circuit now seating 146,000. They have the benefit of one of the largest the world's largest high definition video board at the track. The video board measures approximately 200 feet (61m) wide by 80 feet (24m) tall, containing over nine million LEDs. Situated between turn 2 and 3 along the track's backstretch, it has since been surpassed in size by the video board at Texas Motor Speedway.

The circuit diversified into Indycar Racing from 1997 to 1999, but a crash on lap 61 led to a car losing a wheel, which was then propelled into the grandstands by another car. Three spectators died and eight others were injured in the incident. The race was canceled shortly after and the series has not returned to the track since. Catch fencing at all Speedway Motorsport tracks was increased in height following this incident.

Another tragedy occurred following the 2000 NASCAR All-Star race, when a pedestrian bridge from the track to a nearby parking lot collapsed, injuring 107 fans when an 80-foot section fell onto the highway below. Investigators found that the bridge builder, Tindall Corp., used an improper additive to help the concrete filler at the bridge's centre cure faster. The additive contained calcium chloride, which corroded the structure's steel cables and led to the collapse. Nearly 50 lawsuits against the speedway resulted from the incident, with many being settled out of court. The bridge has since been rebuilt by Tindall Corp. at no cost to the Speedway.

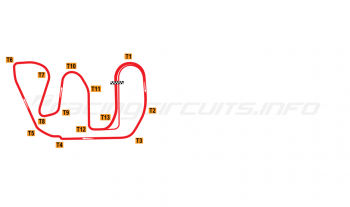

For 2018, the second of the NASCAR races switched to using the 'Roval' course, which combines much of the infield road course and almost the full oval circuit (only 400 feet of the full oval are not used by the 2.4 mile combined course), with additional chicanes on the front and back stretches. The Bank of Amercia 500 has thus become the first road course in the NASCAR play-offs - unusually for a US race, the '500' refers to the race distance in km, as the event will take place over 130 laps.

For 2019, the back stretch chicane was modified to create additional passing opportunities and more side-by-side action. Parts of the inside wall near oval Turn 3 were moved back to accommodate more on-track space for the updated chicane, which is now 54 feet at its widest point and features greater run-off areas. The new design had input from NASCAR drivers Kyle Larson, Ryan Blaney and Justin Allgaier, as well as former Formula 1 racers Alex Wurz and Max Papis. The track length was unaffected by the changes.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

- Charlotte Motor Speedway, 5555 Concord Pkwy., South Concord, NC 28027, USA

- +1 704 455 3200

- Email the circuit

- Official website

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 6464

Plan a visit

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.