Bridgehampton

Circuit Overview

In the pantheon of 'lost' racing circuits, Bridgehampton on New York's Long Island must rank as one of the most sorely missed. One of the most thrilling and challenging of the road courses which sprang up in the late 1950's to cater for the boom in sportscar racing, it had a chequered history of financial difficulties, before finally being swallowed up by the seemingly endless series of golf courses that proliferate the Hamptons.

While most of the course has gone, this section has been at least preserved as a time capsule by the current owners, complete with its original wooden footbridge and faded advertising signs.

Circuit History

Bridghampton's racing story actually began many years prior to the establishment of the road course. In 1915, the town's annual Fireman's Fair brought together some of the early pioneers of road racing to compete against locals in homemade or modified machinery. Names such as John Ambrose, Moosie Thompson, Court Rodgers and Norris Hoppin were among the field who competed on a roughly rectangular 3-mile course on roads around the town.

Running anti-clockwise, the circuit began on Montauk Highway, before turning left onto Halsey Lane, left onto Pauls Lane, left onto Ocean Boulevard, and left back onto Montauk Highway to the start finish. Slow by modern standards, the racers hit average speeds of up to 50mph as they traversed the course.

Racing continued through to 1921, when World War One brought the curtain down on this first chapter. It would take until after the next global conflict for motorsport to resume in the Hamptons, with the help of one of its hero pilots.

New course heads the sportscar boom

Bruce Stevenson of Sagaponack came back from the European conflict with an appreciation for the light sportscars that proliferated overseas, in stark contrast to the big block behemoths that were being offered by the Detroit motor firms. He purchased an MG TC and began pondering where he could race it. If the roads around Bridgehampton were good enough several decades before, it seemed likely that they could be so again...

Forming the Bridgehampton Road Races Committee, Stevenson along with three leading sports clubs decided to revive the road races of old in 1949, this time largely as a playground for European sports cars. In doing so, they established a template which would see sportscar racing explode in popularity across the USA.

The original 1915-21 course was no longer felt to be suitable, so a new circuit was drawn up by Stevenson and local businessman B.J. Corrigan, which excluded much of the original layout, with only part of the Ocean Road section being incorporated. This was where the start line was located, next to the Bridgehampton Golf Club, before racers headed out around a clockwise four-mile circuit. Heading north to Sagaponack Road, the racers then turned east to Sagg Main Street, south to Bridge Lane, west to Ocean Road, and back to the starting point. Among the highlights was a hump-back bridge, while long straights would see the racers hit speeds of over 100mph.

The first race was held on June 11, 1949, with more than 50 entrants, including a veritable who's who of the contemporary racing scene. The presence of Briggs Cunningham, George Rand, the Collier brothers and George Weaver in sleek sportscars drew in the crowds and a plethora of New York celebrities, establishing the event early doors as a firm favourite. George Huntoon won the inaugural race in an Alfa Romeo 8C.

Over the following years the races expanded, with entry lists growing to over 180 cars, while crowd sizes steadily increased, with some 40,000 turning out in the final years. Tom Cole won the races in 1950 and '51 driving Allards but for 1952 the event had become part of the SCCA National Sports Car Championship, adding further to the prestige. The next two victories would fall to the more exotic Ferrari 340 of Bill Spear, though the latter came after racing was stopped early following an incident where Harry Grey's spinning Jaguar C-Type injured three spectators who were standing in a prohibited area.

Racing on public roads banned

It would prove the final straw for the event, which has already been marred by tragedy when Bob Wilder lost control of his Allard at the bridge, crashing to his death. Road & Track magazine's David Leigh was scathing of the race organisation in his write up of the event, describing it as mismanaged and correctly forecasting it was to be the last of the classic road races.

Combined with the events at Watkins Glen the previous year, in which another spectator was killed, the calls for change in the name of safety were echoing loud and clear. New York State legislators were soon to act, passing a bill which banned road racing altogether.

Undeterred, the Bridgehampton set began planning a new home for their activities, when the Bridgehampton Road Races Corporation (BRRC) was formed to develop a permanent circuit in the area. This brought together New York businessmen with local farmers, landowners and enthusiasts, with a board of directors comprising representatives from the Motor Sports Club of America, SCCA and the Long Island Sports Car Association. Another key member of the group was Henry 'Austie' Clark Jr., proprietor of the Long Island Automotive Museum.

An ideal spot was found on a hilltop site overlooking the Sag Harbour, further north of the roads previously used for racing. Called Noyack Hills but known locally as 'the backwoods', the site had originally been part of lands granted to local settlers by King James II in 1685 and was later parcelled out to farmers for hunting and foraging.

This unusual history posed something of an obstacle to development, as property records showed hundreds of owners of small plots of land, all of whom would have to be located and bought out if the dream of returning racing to Bridgehampton was to be realised. Shares were offered in the new venture at $5 each to passers by from a card table outside a local meeting spot. The perseverance of the Corporation paid off as over the next few years almost 600 acres were purchased from the various owners, at an average of $60 per acre.

A new circuit rises

With the land secured, attention now turned to fashioning the circuit, with the promise of a layout "second to none in the world". The woodlands were cleared and two engineers for the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, Al Piloff and Jake Bohn, were brought in to draw up the engineering plans. The final design, however, owed a great deal to the judgement of Ercole Colasante, an immigrant racer and road builder from Italy, who fine tuned the layout with his bulldozer.

What's in a name?

The final corner of the track is called Arents Turn and marks the spot where American Tobacco heir George Arents III demolished a brand new Ferrari while testing the unopened course in 1957. Fortunately he was rich enough to buy, repair and replace the Italian machine and earned himself a corner name into the bargain!

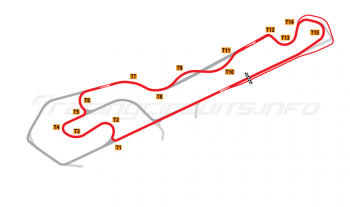

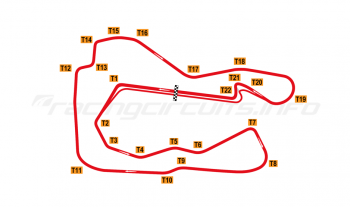

And what a layout it turned out to be. Stretching out over 2.850 miles, the course followed the topography of the land, plunging through 130 feet of elevation changes and 13 sweeping corners, including a seemingly never-ending banked hairpin bend at the lowest part of the course. It was once rather memorably described as being "shaped like an abstract whale".

No less than Sir Stirling Moss described Bridgehampton as "the most challenging course in the States", with its fast and plunging first corner in particular proving a major test of any driver's mettle. Mario Andretti was similarly in awe: ''Turn One was an unbelievable corner because it was blind, and you just fell out. It could scare the bejesus out of anybody.''

The circuit opened in 1957 (though construction was not fully complete at this stage) with an event held by the Harley Davidson Dealers' Association, who organised a Sportsman's Road Race with free admission to spectators arriving on motorcycles. The inaugural event on four wheels was held three weeks later, a round of the SCCA National Sports Car Championship. As would become the norm over the next seven runnings of the event, the feature race was won by Walt Hansgen, running for Briggs Cunningham.

That first weekend of sportscar racing saw a crowd of 30,000 turn out, with cars reportedly parked more than a mile away from the track entrance. New York celebrities such as John Norwood, Vince Sardi and John Weitz were among the competitors, while professional drivers on the grid included Hangsen and Cunningham and future World Champion Phil Hill, among a field of 139 drivers.

A very different field of drivers was added to the calendar in 1958, when the "Good ol' Boys" of NASCAR came for what is considered the first ever non-oval road course race for the stock car series. A 100-mile Grand National race on August 8 featured star names such as Buck Baker, Junior Johnson, Lee Petty and Fireball Roberts. It was Jack Smith, however, who took home the $800 winning purse.

Financial worries lead to new management

Despite the on track successes and the good reception the circuit received from its investors and spectators alike, financially The Bridge was always teetering towards difficulty. The overall management left something to be desired, as many of the large crowds that came to watch the races had not paid for the privilege, having taken the unsurprising shortcut of walking through the woods to avoid toll gates. Add in the bank loans and other repayments due - not least to road builder Ercole Colasante - and it soon became clear that a new direction was needed.

In 1959, the BRRC turned over the running of the circuit to a new operation, Bridgehampton Enterprises Inc, which had been formed by Ed Krom, Lou Figari, Art Schmidt and Henry Treadwell. Working without a fee, the four businessmen began to turn the finances around, reducing debt and developing spectator amenities. Among the advances were the addition of the Lowenbrau pedestrian bridge over the main straight, as well as the Circuit Club paddock next to the timing and scoring tower.

Overlooking the main straight towards the pits also sat 'new' grandstands - in reality these were an astute salvage job, having been imported from the Polo Grounds, the demolished home of the New York Giants and New York Mets.

The headline event was the Bridgehampton Sports Car Races, which were a part of the SCCA National Championship before shifting to the professional United States Road Racing Championship in 1965. Regional races would be added in 1958, while the event awarded the resurrected Vanderbilt Cup in 1965, '67 and '68.

Another major event was the Bridgehampton Grand Prix, which from 1962 became the circuit's first ever FIA-sanctioned race, known as the Double 400km, a round of the World Sportscar Championship. Bob Holbert won in a Porsche for the first of the races on September 15 for the two-litre cars, while the next day saw Pedro Rodríguez win in a NART Ferrari in the above two-litre class.

The World Sportscars would continue as the headline attraction until 1966, when Can-Am took over to hold sway for the next four years. Bridgehampton was the venue for the only Ford-powered win in Can-Am history, when Dan Gurney took his Lola T70 to victory in that debut race, which also saw the introduction of Jim Hall's be-winged Chaparrals.

Trans-Am was next to arrive in 1968, with Mark Donohue winning the inaugural event in Roger Penske's Chevrolet Camaro - one of 10 victories in the category that year. He also took victory in the 1970 event, held during a major rainstorm that would also turn out to be the last major professional event at the circuit. Only a round of the fledgling IMSA series - at that stage a much more amateur affair - would follow in 1971.

Beginning of the end

The march of time was not proving kind to the course. Ravaged by hurricanes and with lightning strikes hitting wires exposed by eroding sands, maintenance was a constant worry. In truth, the track didn't have the finances to modernise; barriers only existed along the pit straight, with the remainder of the course protected only by the sandy verges, just as they had been at its opening over a decade earlier.

Worse was to come, thanks to the homes which were springing up ever closer to the track with every passing year, leading to more and more noise complaints. Eventually, the town's governors included the circuit in an anti-noise law which was originally aimed more at discos than motorsport venues. It meant unmuffled professional events would have to cease, causing further pain to the circuit's finances. In an effort to recoup this lost income, The Bridge began to host more and more amateur club races, to the point where something was being raced virtually every weekend - only adding to the noise complaints.

The circuit struggled on into the 1980s, with many of the original stockholders showing an inclination to sell up and cut their losses, thanks to the ever-appreciated value of the land. For sale boards did indeed eventually go up and the circuit looked doomed as the developers circled for the kill. A further blow came in 1981 when the Lowenbrau Bridge came crashing down, never to be replaced, though the track struggled on to make sure that its programme of club events could continue.

Even 'Ol' Blue Eyes' can't save The Bridge

A new organisation was formed in order to save the facility for racing. The Friends of Bridgehampton (later to become the Bridgehampton Racing Heritage Group) aimed to persuade the new crowd of wealthy amateurs to buy out the by-now elderly existing stockholders in the hope of tipping the balance away from those who wanted to sell out. They had a high-profile supporter in actor Paul Newman, for whom The Bridge had become a favourite haunt for his own racing exploits.

A potential saviour was found in Bob Rubin, a wealthy Wall Street trader and car collector, who heard the Friends' pitch at a Ferrari Club driver's meeting and immediately set out to buy out the shares. After several months of successful negotiation, a shareholders meeting agreed the sale of the property to Rubin, who eventually would become the sole owner.

Rubin had the dream of creating an East Coast equivalent to the popular vintage events at Laguna Seca and set about trying to gain exemptions to noise abatement regulations. Despite numerous efforts, the Town Council was unswayed, having seemingly set its stall out that land speculation and not tourism was to drive forward the local economy.

Eventually, Rubin had enough and announced that, if the council didn't want to support racing, he would build a golf course and housing on the site. Sadly for the racing enthusiasts, the town politicians readily agreed and the writing was on the wall for the racing circuit.

This came despite some unlikely new - and vocal - opponents of the golf course; the very same residents who had complained about the noise! This time, their concerns focused on the impact of the golf course on their drinking water. The circuit acted as a prime recharge area for fresh water in the Hamptons and so there was concern that the golf course would pollute these.

An unlikely alliance was formed between the residents' Group for the South Fork and the Bridgehampton Racing Heritage Group, who filed lawsuits against the golf course plans. Cars in the local area began sprouting bumper stickers saying: 'Noise pollution is transient - water pollution is permanent'.

Even the National Register of Historic Places got in on the act, decreeing the Raceway as a historic site, though this had little impact on the town council. Despite numerous public hearings at which opposition was vocally demonstrated by residents, the politicians approved the golf course plans in 1998. Racing was finally to come to an end.

The SCCA had soldiered on with amateur club racing through to 1997 and thereafter a few further club events took place the following year, with a final hurrah in the spring of 1999, after which the bulldozers moved in.

Bridgehampton today

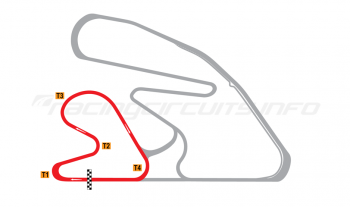

To his credit, Rubin has retained more than a mile of the circuit as an access road to the golf course. The main straight and Turn One, plus the run down to Millstone, are retained, as is the bridge overlooking the downhill sweeper, complete with faded Chevron Gasolines branding. On the outside of the turn a stretch of double-layer Armco barrier serves as an extra reminder of its former use, with a wooden flag stand beyond.

The golf clubhouse itself is a rather spectacular building which enjoys views of the Peconic bay and is home to Rubi's car collection. It forms something of a museum to the motorsport past of The Bridge, though with an initiation fee of around $1 million to join the golf club itself, it's a view only the well-heeled get to share.

Rubin has, however, been able to organise the vintage sportscar event he once craved. 'The Bridge presented by Richard Mille' launched in September 2016, bringing together nearly 60 post-war sports and racing vehicles on the greens of the golf course. The inaugural gathering united the worlds of cars and art in a new and original way and paved the way for the following years, hosting up to 160 automobiles with an extended art component featuring revered galleries of Manhattan.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

This is a historic circuit which is no longer in operation.

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 595

Location Information

Bridgehampton Race Circuit was located close to Noyak, in New York's Long Island, USA. Today, The Bridge Golf Club occupies the site of the former raceway, though the main straight and section through Turn One and Two have been preserved as the access road to the club house.

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.