Birmingham Superprix Circuit

Circuit Overview

For five glorious years the streets of Birmingham reverberated to the sounds of racing cars, as Britain's only contemporary closed public road course enjoyed its moment in the sun (and a hurricane, but more of that later). While it was never quite going to live up to the hype of being the 'Monaco of the Midlands', it did help inject a bit of glamour into England's second city as it looked to re-position itself from its industrial past.

From 1986 through to 1990 the circuit hosted the Superprix for F3000 machinery, attracting unusual attention to the category, with live television coverage of the event, including the support races for the British Touring Car Championship, Formula Ford and other sports car and saloon car races.

The event sadly petered out when the organisation was put out to tender after the 1990 race and there were no bidders. So closed a chapter of British motor racing which lives long in the memory, despite there being virtually no sign on the streets today that a race ever took place!

Circuit History

While the first race would not take place until 1986, the actual idea of hosting a race around the streets of Britain's second city was first mooted more than two decades earlier. Two men who would go on to play significant parts in the history of Birmingham Superprix had both entertained the thought of high-powered racing cars competing for glory in the city centre, much as they did at classic events on the continent.

The first was Birmingham City Councillor Peter Barwell. A racing enthusiast, he claims that the idea first came to him in 1961, while he was spectating at the Le Mans 24 Hours race in France. Whatever the actual merits of this claim, he would go on to be a prominent and significant supporter of the efforts to establish the race in his home city.

The other key player was businessman and music club owner Martin Hone, himself a sometime sportscar racer of some note. Having set up the Opposite Lock Club in the city as one of the premier nightspots in the 1960s, he was invited to one of Birmingham City Council's sub-committees to discuss ways to boost the city's reputation. Sensing his opportunity, he asked the assembled councillors: "As a city internationally famous for the manufacture of cars but with not many 'firsts' to our name, how about I organise the first-ever street race in Britain?"

It would be fair to say that the proposal was not exactly welcomed with open arms, not least because of the very apparent obstacles to making it a reality. Putting to one side the not insignificant issue of financing such a venture, there was also the thorny problem that a road race was at that stage illegal, thanks to an Act of Parliament having been passed as recently as 1960 banning any form of motorsports on the public highway.

Getting a race off the ground would therefore require not only cross-party support among the City Council (and, as time went on, the newly-established County Council) but also of Parliament, as new legislation would be required in order for racing to be permitted once again on public roads. It all seemed highly far-fetched.

Hone, however, was doggedly persistent. While numerous meetings with councillors continued behind the scenes without much support being garnered, he continued to lobby prominent names within the motor racing fraternity to lend their support. Among those to provide endorsements were Stirling Moss, Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart.

A festival is born

Then, a piece of luck came Hone's way; Councillor John Silk, chair of the Entertainment Sub-Committee of the City Council's General Purpose Committee, dreamed up the idea of a festival to promote the city, scheduled for August 1970. Hone proposed a motoring pageant as a way of celebrating Birmingham's prominent motor industry heritage and the council agreed, appointing him as Festival Liaison Officer. It was the first significant turning point and helped cement Hone's credibility.

The 14-day Birmingham Motoring included a veteran car run and themed demonstrations of vehicles on a 2.1 mile course around the ring road. A parade celebrating Grand Prix racing brought the event to a close, led by Stirling Moss in a Lotus 18. The cars crept round at no more than 30mph; any faster and they would have broken the still-in-force speed limit! The crowds loved it, and so did many on the council, including Lord Mayor Neville Bosworth.

Thereafter, Hone and Barwell began discussing a real race with more seriousness, with the result that Barwell wrote to John Silk to formally table the idea before the council, initially receiving a favourable response. Research by Hone, including a trip to the Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuic Park, led to the presentation of a detailed white paper - which was then met with horror in the council chamber, with members fearing a colossal cost was being heaped upon them. For every step forward, the race seemed to take two steps back.

And so it went on for several years more. Further demonstration events featuring contemporary Formula One cars - and indeed star names such as Moss, Jody Scheckter, James Hunt and Derek Bell - were held in the late '70s and early-1980s, each gaining more momentum than the last. Eventually, the authorities were persuaded enough that new road racing legislation could be presented to Parliament in 1986 - only for it to be thrown out without discussion as it was parceled up within a Bill which had measures about municipal trading which did not find favour with MPs.

Formula One on the streets

Nevertheless, Hone was undeterred and in 1976 arranged for a further demonstration run around the Bull Ring by Patrick Neve in a works Brabham F1 car. The event was no more than a publicity stunt, but as it was the height of 'Hunt-mania', the clamour for any F1 association meant the BBC's Nationwide programme came along to film it. Neve found he could not keep the Brabham to anything like as low as 30mph but was fortunate that the supervising West Midlands Police Assistant Chief Constable William Donaldson was happy to turn a blind eye...

The impetus for a proper race finally came in November 1984, when the Birmingham Road Racing Bill was passed by Parliament. The reality of high-speed racing returning to the nation's streets was just around the corner. There was however a 'sunset clause' negotiated with the opponents of the bill - the race would have five years to show a profit or be called off. Other conditions included holding the event as a two day-affair only, over a Bank Holiday weekend in August, with strict limits on the numbers of days before and after that barriers could be in place.

After some further parliamentary shenanigans, the Bill finally received its Royal Assent in October 1984, becoming the rather officiously titled Birmingham City Council Act 1985. The race was now on - to be titled the Birmingham Superprix in recognition that, as a non-F1 race, it could not use the more familiar Grand Prix moniker.

A new promoter is chosen

Much to Hone's surprise, the city council decided to put the contract to organise and promote the first race out to tender. Despite his years of expertise in laying on events in Birmingham (and organising another street race in Dubai) Hone was not successful, and was left to watch his 'baby' brought into the world by foster parents.

The inaugural Birmingham Superprix, a round of the FIA Formula 3000 Championship, was thus staged by sports marketing company CSS (perhaps not coincidentally a key player in Birmingham's bid for the Olympic Games and headed by well known motorsport personality Andrew Marriot) and the British Racing and Sports Car Club on Sunday, August 24, 1986.

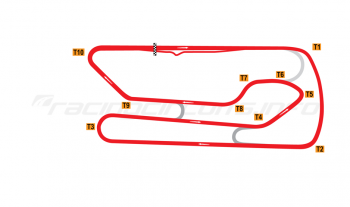

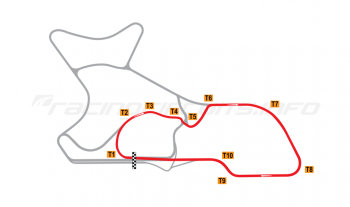

The course was centred on Bristol Street, running down the Belgrave Middleway to a hairpin formed out of a roundabout before heading back up the other side of the carriageway to a sweeping right hand bend onto Pershore Street, before returning back onto Bristol via Pershore Street and Bromsgrove Street. The local Ford dealership was handily located to provide a rudimentary pit lane and garage area, with a large area at the rear where repairs could be carried out. The main paddock area was, however, located in a multi-storey car park on Pershore Street, providing one small parallel at least with Monaco!

In order to discourage the racier locals from attempting to lap the circuit in the road cars at speeds exceeding the limit, the track was deliberately designed to run anti-clockwise and thus against the normal direction of the traffic flow.

What's in a name?

To gain income from the race, naming rights to the corners were all sold to sponsors, meaning, but for a few exceptions, they would often change from year to year. Birmingham City Council scored an early coup by securing title sponsorship for the race from car parts company Halfords, who paid £70,000 for the privilege and also got first dibs on which corner to name. They chose the hairpin, figuring that as one of the more visible and slowest corners, they would get more TV coverage and airtime. Ferodo was also a constant sponsor throughout the five races, but the likes of British Telecom, Pye, Zenith Data Systems and Cavendish Finance were among those to lend their names in at least one of the years of running.

The only non-sponsored name on any part of the circuit (the street names themselves aside) was the rise uphill rise to the Halfords Corner, which was named Peter Barwell Hill after the councillor who had championed the cause of the race. Sadly, there was no similar recognition for the tireless efforts of Martin Hone.

Racing gets underway

Or rather it doesn't. Proceedings got off to a faltering start when all of the barriers had to be checked after rumours circulated that locals had removed some of the bolts. It was also discovered that others had been incorrectly installed, with the overlap between the metal railings in the wrong direction. A delay of two-and-three quarters ensued, during which the F3000 drivers engaged in an impromptu 'Italy vs the Rest of the World' football match in the pits, much to the delight of the otherwise bored spectators in the grandstands opposite.

Finally though, at 11.45am, racing engines fired up and the reality dawned that, after all the years of wrangling and many months of careful planning, the Superprix really was go. John Nielsen had the distinction of completing the first full lap of the new circuit at speed in his Ralt-Honda. His 105.5 mph average speed showed that the Birmingham course was fast for a street course and, while it had the usual lumps and bumps associated with such circuits (especially on the change of camber on entry to the Halfords Corner), it required finesse as well as straight line speed to be successful.

Alain Ferte wrote off his March chassis after striking a loose manhole cover, while Roberto Moreno spun in one of the corners and travelled through the open gates of the wholesale market, fortunately without any harm. It was fortunate indeed that, in planning the circuit, city engineers had had the foresight to envisage this exact scenario and had installed the gates where previously there had been a brick wall...

A hurricane arrives

These relatively minor issues aside, the first day went well in dry conditions. The same could not be said for race day however, when officials had to cope with the torrential downpour provided by the aftermath of Hurricane Charley, which proved a most unwelcome visitor to the Midlands.

When the race finally got under way, there was inevitable carnage and a battle-scarred Luis Perez Sala was declared the winner (minus his nosecone) after Andrew Gilbert-Scott's Lola hit another crashed car and blocked the track. The race was abandoned after 24 of the scheduled 51 laps with half-points awarded.

Future runnings enjoyed better weather and fewer organisational hiccups, but the carnage was just as frequent a factor as before. The 1988 race saw David Hunt (brother of World Champion James) launch himself over a gravel trap, skim the barriers and embed his Lola into the brick wall of the Wholesale Market building behind, several feet off the ground. Happily he emerged largely unscathed, if a little dazed, though his Lola was sheared in two and the wall had a large hole punched through it.

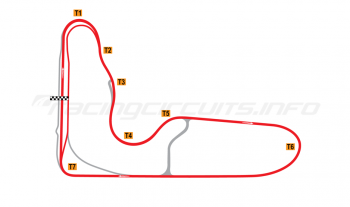

However, it wasn't the on-track antics of the racers that spelt doom for the event. Instead, rising costs and the fact that the number of paying spectators had hit a ceiling of around 50,000 conspired to convince the city council to put the event up for commercial tender after the 1990 race. The track also needed to be lengthened to meet international rules.

Plans for an extended circuit were drawn up, but in the end there were no bids for the tender and the streets of Birmingham reverberated to the sounds of racing engines no more. It was a sad end to what had been an exciting, if brief, chapter in British motorsport.

What was the Superprix's legacy?

Did the event succeed in its ambition to cast a new light on Birmingham, bring new crowds and further investment, transforming its rather drab, post-industrial image? Well, crowds certainly came and there was a certain amount of glamour, but any notion that this resulted in the city becoming a tourist destination must surely be wide of the mark. Let's not forget that the race itself was held in perhaps not the most attractive parts of the city, even if it was practical to accommodate the spectators. That said, it likely brought more economic activity to the area at a time that it likely needed it most - worth far more to the city's finances overall than any numbers on a council balance sheet could show.

Ultimately, it's legacy was negligible. There was no clamour from elsewhere to take up where Birmingham laid off - the acts of parliament saw to that, in that the Superprix was very much the exception to the rule. And in the city itself, there are few now who even remember that racing occurred.

And yet, Birmingham has prospered and this is no more evident than round the route of the old circuit itself. The run down shops and industrial buildings are now giving way to new modern offices, flats and shops, while the Arcadian, with its eateries, bars and nightspots now provides a more welcoming link to the rest of the city centre. Monaco House, next door to Bristol Street Motors, was once a rather uninspiring office block, but has recently been demolished to make way for a more appealing 'New Monaco' development. Even the Wholesale Market has disappeared, moved elsewhere to make room for another new transformative 'gateway' development.

Could the circuit ever be revived? It seems unlikely. Safety standards for street circuits have moved on and the likely disruption modern concrete barrier fencing would bring to the even more congested city centre road network mean it is unlikely to suitable any longer. The current Mayor of the West Midlands, Andy Street, has talked supportively of bringing Formula E to the city, though it would likely need to be held elsewhere. That London now has secured its own Formula E race makes this seem likely to remain little more than a pipe dream.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

This is a historic circuit which is no longer in operation.

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 1262

Location Information

The Superprix course was located in the Highgate and Chinese Quarter areas of Birmingham, United Kingdom. Although the race is long gone, the streets themselves have been little modified in the years that follow, so it is possible to trace (on foot at least) the path the racers took.

There's little tangible evidence these days, however, of a race ever having taken place and you won't find any particular official recognition of the course. However, there are small traces still evident. On some of the side streets that made up the more return leg of the course you can still see the metal covers for the Armco barrier postholes embedded in the edges of the pavement. The top end of Sherlock Street and Pershore Street retain the most, though they are gradually disappearing as pavements get renovated over the years.

There's also the Haden Circus roundabout, which still features 'temporary' concrete barriers to mark the normal carriageway, with the now unused asphalt which formed Halfords Corner covering one half of the roundabout's centre. It's also possible to make out the (now unpainted) concrete kerbing at the junction of Sherlock Street and Pershore Street, site of David Hunt's infamous crash. With the redevelopment of the old Wholesale Market site, it's doubtful how long this will remain in situ.

Gone forever though is the old painted start/finish line, which remained partially visible outside Monaco House on the kink just before Bristol Street Motors until the main carriageway was resurfaced.

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.