Montjuïc

Circuit Overview

Most histories of Barcelona's Montjuïc circuit tend to focus on its short-lived flirtation with Formula One 1969 and 1975, totally overlooking its much longer affiliation with motorcycle racing, not to mention the other four-wheel events which predated the premier category. Breathtaking, fast, dangerous and chaotic certainly sum up many of its aspects but the circuit was much more, posing a real challenge to riders and drivers alike for more than 50 years.

Circuit History

Located on a hill overlooking the Catalan capital, the park in which the circuit was set has long been a site of strategic importance. Roughly translated as 'Jewish Mountain', the remains of a medieval Jewish cemetery have been found in the Montjuïc parkland. Due to its location overlooking the harbour and the Llobregat River, several fortifications have been built, the last of which, the Castle of Montjuïc, was built in the 17th and 18th century and remains today.

The slopes of the Montjuïc were traditionally used to grow food and graze animals by the people of the neighbouring Ciutat Vella. In the 1890s, the forests were partially cleared, opening space for parklands. The site was selected to host the 1929 International Exposition (a World's Fair), for which the first large-scale construction on the hill began. The surviving buildings from this effort include the grand Palau Nacional, the Estadi Olímpic (the Olympic stadium, built as part of a failed bid for the 1936 Olympics) and the ornate Font Magica (Magic Fountain).

Montjuïc's circuit wasn't, however, the first circuit to host racing in the region. The first racing occurred in 1908, when the Catalan Cup was run on the roads over public roads from Sitges to Canyelles to Vilanova i la Geltrú, and from Mataro to Vilassar de Mar and Argentona. In 1922 and 1923 the Real Moto Club de Catalunya ran the Penya Rhin Grand Prix over a 9-mile circuit around the town of Vilafranca del Penedès, until it was replaced by a short-lived purpose built circuit, the banked Autodromo Sitges Terramar, which held its only major race in 1923 before falling into financial difficulties.

First racing takes place

So it was that the 'Magic Mountain' came to prominence. On Christmas Day 1932, the Association of Motorcycling Runners of Catalonia organised the first Catalonian road racing championships with a race that started from the Parc de Montjuïc and headed down to the harbour. This may well have proved the spark that the organisers of the Penya Rhin Grand Prix needed. A 10-year absence had been spent trying to find a new home and the Parc de Montjuïc seemed ideal. So it was on the now familiar course outline that a revived Grand Prix was scheduled for June 1933.

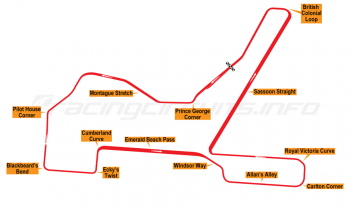

The course followed the streets around the base of the hillside. Starting under the grand staircase of the Palau Nacional, racers blasted off uphill through a series of corners that brought them past the Font de Ceres and then on through sweeping curves up and over the crest of a hill by the Olympic Stadium, the highest point of the circuit. A tight downhill left-hand hairpin then led through a series of slower corners back to the start and finish. The track surface at this point was a combination of cobblestones and asphalt with tramlines crossing it at various points, adding to the challenge.

Perhaps this would have been little more than a domestic race which may not have drawn huge attention, were it not for the presence on the entry list of 'The Flying Mantuan', Tazio Nuvolari in a Scuderia Ferrari Alfa. The Italian great was quite a draw and so entries from Bugatti and Nacional Pescara soon followed. Nuvolari performed admirably in his Alfa-Romeo 8C, dominating the early stages and setting fastest lap, but had to settle for a fifth place finish after problems led to a long pit stop. He finished two laps down to the privateer Alfa of winner Juan Zanelli.

The Penya Rhin Grand Prix would last just three more years at Montjuïc (with Nuvolari getting his revenge and winning the final event in 1936) before the Spanish Civil War intervened. With the world soon also plummeting into global conflict, all thoughts of racing were put on the back burner.

Racing returns

Racing would eventually return in 1946 to the slopes of the mountain, but the grand prix had departed to Pedralbes, so it was local touring cars and road vehicles that took part in the races. The spectators lapped it up all the same.

It was the two-wheeled brigade that was first to notice Montjuïc's potential on the world stage. In 1951, the circuit hosted the opening round of the FIM World Championship, with races for 500c, 350cc, 125cc and Sidecar classes. Umberto Masetti would win the 500cc feature race on board a Gilera.

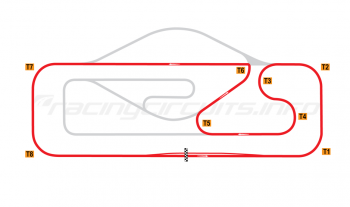

The debut of the World Championship would see the first course alterations in the circuit's history, with the bikes turning sharp left at the fountain and heading along Avinguda dels Montanyans, through a series of corners at the back of the Palau Nacionale, before rejoining the Avinguda de l'Estadi and heading in the opposite direction to normal. A further diversion brought in roads surrounding the Olympic Stadium, before rejoining the classic circuit at the Anguela de Miramar. The course length was now 3.749 miles.

For the following season's race, the track was again altered, with the section along Avinguda dels Montanyans eliminated and a simplified diversion around the stadium leaving the lap length at 2.613 miles. The race was also switched to the season finale, with British MV Agusta rider Graham Leslie beating Masetti to the win in the 500cc class.

The experimentation with alternative layouts was ended in 1953, when the classic route was restored, with very little variation thereafter for the remainder of its racing use. The World Championship continued its visits through to 1955, the same year that saw the launch of one of the mainstay events on the Montjuïc calendar, the 24 Hours for motorcycles. This would go on to be a staple of the FIM Endurance Cup from its formation in 1960, then the European Endurance Championship from 1976 and finally the World Endurance Championship from 1980 until 1982.

After a five year gap, the Motorcycle World Championships would return, from 1961 to 1968 with only events for the 125cc and 250cc classes, before the new Jarama circuit at Madrid opened and the event was shared between the two venues on alternate years until Montjuïc hosted its final event in 1976.

Four-wheeled revival

Car racing, meanwhile, had undergone something of a revival in the 1950s, with domestic car manufacturer SEAT behind a push to resurrect the local racing scene. From 1954 it introduced the Montjuïc Cup for sportscars and also the Nuvolari Trophy for smaller classes of road cars. By the 1960s this had blossomed further, when the RACC joined forces with the Penya Rhin group to gain greater recognition for the Nuvolari Trophy and then the Juan Jover Trophy from 1963 onwards. This saw the GT ranks hosting the crop of the major manufacturers while Formula 3 cars were introduced to the Juan Jover Trophy in 1965. Italian racer Giacomo Russo (competing under the pseudonym 'Geki') was the aggregate winner of a two-heat affair in a race that proved a tremendous success.

The following year saw Montjuïc hit further new heights, when the cars of the Formula 2 circus made the short trip down the road from their traditional stop at Pau to take part in the Gran Premio de Barcelona, the new headline act of the Juan Jover Trophy. Suddenly stars such as Jim Clark, Jack Brabham, Graham Hill and Jackie Stewart were on the starting grid and the event had a new found prestige.

The location of that starting grid was in a new place, as were the pits. Redevelopment of the Avinguda de l'Estadi created a slightly straighter section which allowed for a new pit lane (albeit not yet separated from the circuit by anything more than a painted line). It was from here that car races would now set off, though bike races - including the 24 Hours - would continue to use the original pits and start position.

Despite a rain shower, the crowds left thrilled after a race-long battle saw Jack Brabham take victory ahead of the Tyrell-entered Matra of Stewart, with Denis Hulme rounding off the podium in third. Successive years saw further entertaining F2 battles, with Jim Clark winning in 1967 and Jackie Stewart in 1968.

Formula One arrives

Ironically, it was the arrival on the Spanish racing scene of the new Jarama circuit at Madrid which paved the way for Montjuïc to gain its chance at the summit of four-wheeled racing. Jarama was everything Montjuïc was not; modern and designed to the latest safety standards, if a little boring by comparison. However, the politics of the day decreed that the newly-revived Spanish Grand Prix should be alternated between Madrid and Barcelona, so Montjuïc was suddenly in the frame.

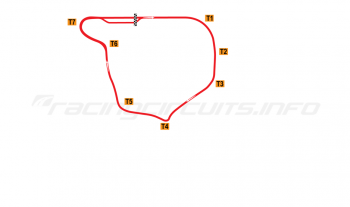

Thus it was that the stars of the premier class would head out onto Montjuïc's streets in 1969, 33 years after they had last done so in the pre-war events. To comply with safety standards, the track was by now fully circled by Armco barrier, with the pit lane now permanently separated from the race circuit. The paddock was located inside the old Olympic Stadium, the internals of which were at this stage largely in disrepair.

The race would prove to be the last of the high-wing era of Formula One, where aerofoils were directly mounted to the suspension by thin spindles. It certainly created downforce but the stresses of cresting the top of the hill by the stadium proved too much; first the rear wing broke on Graham Hills Lotus, causing him to crash into the barrier, then team-mate Jochen Rindt suffered the same fate several laps later, crashing at the same spot and hitting Hill's stricken 49B. It was fortunate that neither were seriously injured.

Chris Amon took the lead until an engine failure robbed him of victory; a consistent Jackie Stewart thus added the Formula One trophy to his Formula Two one from the year before. To no-one's surprise, the high wings were banned with immediate effect.

Tragedy unfolds

Worse disaster lay in wait, however. While the 1971 and 1973 races were largely without major incident, safety and the general organisation of the races was becoming more and more of a concern. The rising speed of the 1970s cars, complete with slick racing tyres, meant that circuit safety was becoming an ever-present concern. When the drivers turned up for the 1975 race, they were horrified by what they found; the safety barriers and catch fencing were in a shocking state, with loose or missing bolts and mounting posts that could be rocked easily with very little force.

Demands for change were lodged with the organisers immediately, though with around five miles of barrier and a small team of workers, the task looked (and was) herculean. Saturday morning dawned with little improvement and it soon became apparent that the teams would have to pitch in too. This made more significant headway, with a feeling that around 90% of the barriers now being fully satisfactory, especially at the most dangerous points of the course.

This did little to placate the drivers, however, and talk of a boycott was heard around the paddock. With a revolt on their hands, the race organisers hardened their resolve. With the entire paddock located in the Olympic Stadium, they announced that unless teams fulfilled their contractual obligations to race, legal action would follow. Spanish police thus would impound all cars and equipment pending court hearings, bringing the whole Formula One circus to a halt. With the paddock located inside the Olympic Stadium this could be accomplished by locking the gates and in out in mere minutes.

The teams panicked and driver unity dissolved as threats of financial penalties or cancelled contracts were bandied about. Drivers were told, however, that they could complete their obligations if they circulated for a minimum of three laps. World champion Emerson Fittipaldi (among the most vocal of the drivers) did just that, turning his laps at slow speed and promptly heading to the airport. His brother Wilson and Arturo Merzario did even less, pulling into the pitlane at the end of the first lap.

The remainder of the field, however, soon found their competitive instincts taking over. A melee at the first corner eliminated the Ferrari of Lauda and damaged team mater Regazzoni's car, along with the Parnelli of Mario Andretti and the March of Vittorio Brambilla. James Hunt took the lead for Hesketh before hitting oil and careering into the barriers. Damage from the first corner eventually accounted for Andretti, leaving the Hill of Rolf Stommellen as an unlikely leader.

Then on lap 26 disaster happened. As Stommellen crest the brow of the hill at the stadium, his rear wing broke, pitching the car across the circuit at 160mph, glancing the Brabham of Carlos Pace and becoming airborne. It then skimmed the barriers on the other side and slammed into a lamppost. It was a scene of absolute carnage, with two spectators, a photographer and a fireman all killed instantly. Stommellen sustained a broken leg, wrist and several cracked ribs.

Still the race continued on; the errant Embassy Hill racer had taken out TV and phone cables meaning news of the accident only reached the pits ten minutes later. The race was eventually red-flagged four laps later with the McLaren of Jochen Mass in the lead; he was declared the winner (his sole F1 victory) and half points awarded. The race was also notable for another first; sixth placed finisher was Lella Lombardi, the first and to date only female points scorer in World Championship history.

The tragedy brought condemnation of the circuit, though perhaps the greatest problem lay with the race organisation itself. Either way, it was clear that the Montjuïc circuit's days of hosting car racing were over with immediate and brutal effect.

Two-wheeled racing continues

This wasn't, however, the end of the Montjuïc story. Despite the events of four wheels, motorcycle racing still deemed the circuit to be safe enough for its purposes and the fabled 24 hours continued. What saved the race was its popularity with the public, helped by the exploits of home-grown heroes such as Benjamin 'Min' Grau, Angel Nieto and Salvador Cañellas.

In truth, safety standards were in many ways worse, with hay bales still being the primary means of stopping errant racers from hitting the trees that lined the route. In more straightened financial times even these would be in shorter supply... Motorcycle riders, however, tended to have a different outlook to their car racing brethren: "You knew a crash meant not only hitting the floor but also something else, some other obstacle," observed Cañellas. "I loved it!"

British rider Chas Mortimer claimed his only World Championship victory at Montjuïc and had a similar opinion. He would later tell the Daily Telegraph: "The only place you could really hurt yourself was on the fast left and right-hander onto the (Formula One) finishing straight. Even on the bikes we were doing 90-100 mph and on the right-hander you'd have to be William Tell to hit one of the strawbales! The chances were that you would hit a tree instead..."

By the early 1980s, even in the tough world of motorcycle racing, questions were being asked as the circuit was found ever more wanting as the bikes themselves grew steadily faster. The World Endurance Championship riders demanded changes and even then some of the top riders boycotted the event in 1982. A slow chicane was introduced over the infamous hump; this was picked out by hay bales and incorporated part of an access road to the stadium.

The end nears

Sadly, this did not alleviate the dangers; in the 1985 race German rider Niklaus Rück crashed and hit a lamppost after sliding for some 200 metres. He was pronounced dead at hospital later that day. Then in the 1986 race Domingo Parés, who had finished second in the previous year's edition, lost control at the exit of Sant Jordi, spinning up at the rear and clipping the wheel of Toni Boronat's bike, bringing the pair down. Parés hit a road sign and was declared dead at the hospital, while Boronat suffered severe head injuries.

The race continued on nevertheless, with the Ducati of 'Min' Grau, Joan Garriga and Carles Carles Cardús running out the victors. The tragedy clearly overshadowed the result and the riders were divided on whether racing should continue.

Sito Pons, who took part just once in 1985, couldn't hide his feelings that the track was no longer appropriate. He told local reporters: "It is unacceptable that in 1986 it is possible that there are trees, streetlights, traffic signs and curbs a few centimetres from the participants. An error, a very human thing, can be paid for systematically with your life."

Also calling time on his participation was winner Joan Garriga, who said that he had thought long and hard but concluded street races were no longer safe. "Many confuse the race with a speed test when it's an endurance event," he said. His teammates, however, were just as adamant the race should go on. Grau felt that the accidents were a matter of fate and he had no opposition to racing again, while Cardús said it would be easy to say after 24 hours that racing should stop but after a year the passion would grow.

Whatever the standpoint of the riders, the 1986 race really did prove to be the final act. With moves afoot to build a permanent circuit and the need to redevelop Montjuïc Park to host the 1992 Olympics, the streets soon rang out year round with the sound of tourist buses and taxis rather than racing engines.

There was a final footnote to the story however. In celebration of the 75th anniversary of the circuit in 2007, a demonstration event was held on the course, albeit punctuated with many temporary chicanes. Called the Martini-Legends, it featured a parade of classic cars associated with the circuit. Among those taking part were Jackie Stewart and Emerson Fittipaldi driving his Lotus 72, while Marc Gene took to the course in a 2006-spec Ferrari Formula 1 car.

A similar event was organised in December 2012, this time called the Montjuïc Revival. This featured 250 classic cars and motorcycles. The event, however, was suspended by Barcelona City Council after one of the vehicles left the track, injuring two members of the organisation, one of them seriously. It was a further indication of the dangers the beautiful course has presented through its lifetime and perhaps another reminder that some things may be better left in the past.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

This is a historic circuit which is no longer in operation.

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 720

Location Information

The Montjuïc circuit was located in Montjuïc Park in the southwest of the city of Barcelona.

Today, all of the roads of the former circuit are still in place, albeit punctuated by a roundabout around the Font de Ceres. There is a monument to the park's racing history at the Joan Antoni Samaranch Olympic and Sports Museum, which is located beside the Olympic Stadium.

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.