Le Mans

Circuit Overview

The Circuit de La Sarthe at Le Mans has become one of the classic courses in use around the world, thanks in large part to the 24 hour endurance race, which has seen it become world famous. Each June, the eyes of the world fall on this eight-mile ribbon of tarmac as one of the great sporting spectacles unfolds, pitting man and machine against the rigours of day and night racing. Nothing else in racing comes even close to matching it.

While there have been many improvements in safety over the years, the circuit's essential character remains.

Today Le Mans is in fact three courses; the famed 24 hour course, which incorporates large sections of public road, and the smaller purpose-built Bugatti circuit, which entertains the crowds for the rest of the year. The third Maison Blanche course was added in the 1970s as a school and track day facility and now is home to a Porsche Experience Centre.

Circuit History

The circuit's origins pre-date its most famous race, however. The first races were held in 1920, when the UMF (Union Motocycliste de France) organised a motorcycle grand prix on a triangular course from the Pontlieue suburbs of Le Mans, along public roads to Mulsanne and back again. In total the circuit measured more than 10 miles and proved a machinery-breaker; of the 31 starters, only four were still running at race's end.

Motorcycle races continued under the auspices of the UMF and the Automobile Club de l'Ouest (ACO) but in 1922, the idea for the 24 hours was born. The secretary of the ACO, Georges Durand, received an unexpected offer of 100,000 francs from the French subsidiary of the Rudge Whitworth wheels company. This was to help facilitate a suitable race, with the money becoming a prize fund for the winner. A free hand was given as to the nature of the race.

Durand pondered the proposal for a while, before realising there was an opportunity to stage an endurance race allowing manufacturers to prove the worth of their road-going cars to an expectant public. Discussions were quickly convened with ACO president Gustave Singher, journalist Charles Faroux and several other officials, and the basic proposal was agreed. Faroux advocated a 24 hour race and was tasked with drawing up the rules and regulations.

Circuit de la Sarthe

On May 26, 1923, a field of 33 cars of 18 different makes headed off for their round-the-clock adventure. Lagache and Léonard ran out as winners in their Chenard-Walker, covering a distance of 1,732 miles at an average of just over 57mph. No fewer than 30 of 33 starters crossed the finish line, which must rank as an all-time record for the event.

The race continued to use this first course with gradual improvements; in 1926 the stretch from Pontlieue to Mulsanne was asphalted for the first time (previously the surface was water-bound macadam), while parking for 3,000 vehicles was also created. The track was shortened for safety reasons in 1929 to avoid the town suburbs that were expanding rapidly. The new link road constructed at the ACO′s expense was named the ′Rue du Circuit′ and bypassed completely the Pontlieue hairpin. Today it is merely another side street lined with housing - with nothing to commemorate its place in history apart from the name.

By 1932, further change was deemed necessary. The revisions of three years previously had failed to solve the problems of the narrowness of the roads as they approached the town, subjecting the drivers and watching public to needless risks as a result. Equally, the ever expanding Le Mans suburbs meant it was becoming increasingly desirable to re-route the course away from housing. In response, the ACO bought land near the pits and created a new 1.505 km link road, which exited onto the Mulsanne Straight at a new corner, Terte Rouge. Built to latest contemporary standards, the new section featured raised earth banking to protect the spectators and included a fast right-hander to start the lap and a series of sweeping 'S' bends. The iconic Dunlop bridges were also erected at this time.

Racing continued through the 1930s, with the race gaining an ever-increasing audience as its importance grew. The outbreak of war meant that the 1939 event was the last for a decade; at war's end France concentrated on getting back on its feet and it wasn't until 1948 that work began on restoring racing. While the roads themselves were in a good enough condition for racing, the ravages of war meant all of the buildings and grandstands needed rebuilding first. Bars, restaurants and shops soon sprung up around the circuit and the 'village' of the Le Mans circuit was born.

The first postwar event was held in June 1949, watched by President Vincent Auriol. A crowd of 180,000 witnessed the birth of another legend that day – the Ferrari of Chinetti and Selsdon took victory on its debut, making its manufacturer the first to win Le Mans in the same year as the Mille Miglia and Targa Florio races. It was the first of many subsequent victories in the 24 hours for the Prancing Horse.

The revival of racing nearly came to an abrupt halt in 1955, when Le Mans was the venue of the worst crash in motor racing history. The exact cause is a subject of conjecture and debate to this day, but the outcome was no less tragic for its confusing circumstances. What is known is that the Mercedes of Pierre Levegh collided with the Austin Healey of Lance Macklin, possibly as it attempted to manoeuvre past the Jaguar of Mike Hawthorn as it slowed to enter the pits. Levegh lost control and slammed into the banking, before the Mercedes somersaulted through the air and into the crowd. Levegh was killed along with 83 spectators and a great many more were injured, some horribly, by the flying wreckage.

It was a disaster of gigantic proportions. Mercedes withdrew from the race, which continued on with an almost callous disregard for the tragedy; much criticism was levelled at Faroux as race director, though he justified his decision to continue by pointing out that stopping the event would only have served to draw crowds to the accident scene, clogging up exits to the circuit and hampering rescue operations. Whatever, it was without doubt motor racing's darkest day.

Despite widespread calls for motor racing to be outlawed (in the end, only Switzerland enacted a ban), Le Mans persevered. The 1956 race was put back to July while the ACO completed substantial modifications. It was clear that a total rethink was required and the whole pit area was remodelled and re-aligned, creating a bigger barrier between track and grandstands. Track width and pit lane modifications also led to a change in radius of the Dunlop curve and also shortened the lap by 31 metres. A new signalling area was also installed at the track's slowest point, just after Mulsanne Corner, to allow teams to show their pit boards to the drivers without causing unnecessary distractions along the start/finish area.

Its reputation tarnished, the following years would see Le Mans gradually rebuild and by the mid-1960s, it was considered one of the most important fixtures once again. Indeed, the epic battles between Ferrari and Ford and later Porsche would help seal its place in motor racing folklore.

In fact, it can be argued that rising speeds as a consequence of the Ford-Ferrari-Porsche battles led to the next major revisions to the course (the building of the Bugatti Circuit in 1965 aside - for more on this see below). In 1968 a new chicane was added just before the pit entrance - named the Ford Chicane - but more substantial revisions were to follow. The circuit was fitted with Armco for the 1969 race, while 1971 saw the separation of the pit lane from the main track with the installation of a dividing wall.

The circuit had still come in for criticism from drivers, particularly at the fast Maison Blanche kink, which had claimed the life of John Woolfe in 1969 and been the scene of a pile-up the following year between three Ferrari 512s (including two works cars). The ACO reacted by bypassing the section altogether, building a new link road for the 1972 season. This permanent section of track featured the Porsche Curves and lead to a revised double chicane ahead of the pits. Further proposals to radically restrict the amount of public road being used were also mooted throughout the 1970s, but ultimately came to nought.

Due to the construction of the new Le Mans ring road on the northern perimeter of the track, Tertre Rouge corner had to be re-profiled in 1979, changing it from a right angled corner to a faster, but more complex double apex curve. The creation of this new section of road required the demolition of the second Dunlop Bridge, while the area of trees on the inside of the corner was completely cleared. Similar changes were required at Mulsanne Corner in 1986; local authorities built a roundabout at the junction to reduce accidents, and the race course was diverted to the inside of the previous layout through a slight kink.

The next changes to the circuit came at the request of the FIM, who were concerned by the speeds on the approach to the Dunlop bridge being attained by bikes using the Bugatti Course. In preparation for the French Grand Prix, a new chicane was added ahead of the bridge in 1987 and this would be used subsequently by all categories on both the Bugatti and La Sarthe courses, slowing speeds dramatically.

The flat out-blast down the Hunaudières Straight was next to suffer at the hands of the bulldozers. In order to comply with an FIA directive on the maximum length of straights, two chicanes were installed in 1990. Many felt this substantially changed the nature of the lap, though it did open up two further overtaking opportunities. In truth, the writing had been on the wall for some time; ever increasing speeds made it likely that some form of change would be necessary. This was emphasised in 1988 when the small WM team hatched a plan to top 400 km/h by maximising their setup for straight-line speed. The plan worked: on June 11, 1988, with Roger Dorchy behind the wheel, the WM P87 achieved the speed of 405 km/h (251.7mph), a record that is unlikely to ever be bettered.

A new pit lane entry was also installed in 1990, which now began at the entry of the Ford Chicane and ran parallel to the main track, complete with its own double chicane. This change was made in preparation for impressive new pit buildings which made their debut the following year. These were located further back from the racetrack to allow for a wider pit working area, ending the often frantic scenes when cars would have to make their way through a throng of photographers and officials down the dangerously crowded pit lane. It also allowed the pit straight itself to be slightly widened.

A small change to the Dunlop chicane also occurred in 1997, moving the turn in further away from the bridge itself to accommodate a larger run off area and also resulting in a slightly different radius at the exit of the Dunlop Corner. In reaction to the spectacular and frightening incidents during the 1999 race weekend when two of the three Mercedes-Benz entries flipped due to aerodynamic instability, the hump in the Mulsanne straight was lowered by 26 feet during the winter of 2000-’01, to reduce the risk of this happening again.

The most radical change since the introduction of the chicanes on the Mulsanne came in 2002, when the entire section between the Dunlop Bridge and the Esses was bulldozed, with the previous downhill straight replaced by a section of fast sweepers. This provided for a better entry to La Chapelle corner on the Bugatti circuit.

Further changes came in 2006, when the Dunlop Curve and chicane were again re-profiled, once more with the track moved further infield to provide greater run off, though without significantly altering the nature of the corner. A new extended pit lane exit, which channelled vehicles exiting the pits into the middle of the chicane, was briefly tried and then abandoned in favour of a more conventional exit before Turn One. At the same time as these modifications, the pit garages were extended to allow grids of up to 56 cars to take part in the 24 Hour events.

The most recent layout alterations occurred in 2007, when Tertre Rouge was once again altered to provide increased run-off, at the same time creating a more flowing curve onto the Mulsanne Straight. Following Allan Simonsen's fatal crash at this corner in 2013, modifications were made to the crash barriers, without altering the track layout itself. Similarly, the construction in 2016 of a new section of public road to bypass the Indianapolis and Arnage corners for safety reasons has allowed this section of the track to become a permanent fixture used exclusively for racing.

The ACO has also rushed forward with plans to complete an additional four grid garages to bring the capacity of the circuit up to 60 cars. Originally planned to be completed in two phases ahead of the 2016 and 2017 races, the quality of entries received for the 24 Hours in 2016 persuaded the ACO to complete the entire project a year early. Two of the garages originally intended for scrutineers will now be used for race teams, with scrutineering moving to temporary facilities ahead of a new permanent home and a new parc ferme being built on the current location of the medical centre in 2017.

Bugatti Circuit

As early as the 1950s, talk began about creating a permanent circuit inside the main 24 Hours course. The costs - and inconvenience of the closure of public roads - limited the use of the full course and there was increasing pressure from local racers and teams for a facility that could be used year-round.

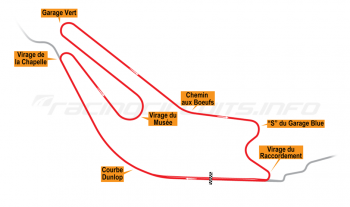

It wasn't until 1964 that the project that would create the Bugatti Circuit got the go-ahead and Charles Deutsch began designing a layout to take advantage of the wooded area to the rear of the main paddock. Supposedly inspired by the silhouette of his left hand, he created a 4.422 km serpentine layout which had the benefit of making use of the 24 Hour circuit's pits, paddock and grandstand facilities.

Just after the Dunlop bridge and part way along the descent towards Tertre Rouge, the new Bugatti course turned right through a tight hairpin and ran parallel to the main course back towards the paddock village area. The then newly-constructed Musée des 24 Heures buildings necessitated the creation of a wide parabolic curve, which turned the course back through more than 180° and onto a new straight to the eastern-most point of the available land. From there another hairpin led onto a long straight with a kink in the middle - the Chemin aux Bœufs - followed by a series of S-bends and yet another hairpin which rejoined the main course just before the pits.

Construction began in the winter of 1964 and was completed by April 1965, aided by the sandy ground helping drain away any rainfall during the construction. Named in honour of Ettore Bugatti, the 2.7 mile course was a modern, if slightly sterile, course but did at least feature the best of contemporary safety measures - though primitive by modern standards, amounting as it did to earth banks, wooden palisades and half-buried tyres as corner markers.

Just two years after its first race, the Bugatti Circuit hosted its one and only Formula One event, with the 1967 French Grand Prix being won by Jack Brabham. "Characterless" was the rather harsh opinion of some drivers, while the meaner American hacks coined the term "Mickey Mouse" circuit. A crowd of just 20,000 turned out to watch and the experiment was never repeated.

Bike racers took to the track more readily and in 1969 it hosted its first World Championship event, with the 500cc class being won by Giacamo Agostini, a feat he repeated the following year. Thereafter throughout the 1970s and '80s, the Grand Prix was shared between Le Mans, Nogaro, Paul Ricard, Clermont-Ferrand and Magny-Cours, before Le Mans was made its permanent home in 2000.

Other high profile two-wheeled events include a 24 Hour race and the Bol D'Or Endurance event and the majority of the subsequent changes to the circuit have made due to safety improvements required by the FIM.

In 1976 the Garage Vert hairpin was re-profiled and squared off to provide additional run off room. The original sand trap was too short and there were numerous occasions where racers would slam into - and sometimes over - the earth bank when things went wrong. The new squared off double apex corner was nothing to write home about.

In common with the main course, 1987 saw the debut of the Dunlop Chicane, while a new 'S' bend was inserted at Chemin aux Boeufs corner, with a realigned straight leading into the final corners at the request of the FIM. The old straight remains in place for those who overshoot the first of the new bends! Two years later came more changes, when the Garage Bleu esses and the final corner were re-profiled, again to create better run off and in preparation for the new pit buildings that were soon to follow. The circuit now fed back onto the main course at the second of the Ford chicanes.

Aside from the various changes to the first corner and Dunlop chicane in common with the main course, the next major change to the Bugatti layout came in 2000, when La Musée corner was tightened and move further infield to create a much extended run off. Next came the major revisions to the Virage de Chapelle in 2002, further changes to the first corner and Dunlop Chicane in 2006 and most recently in 2008, Garage Vert corner was re-profiled for a second time, creating a straighter exit towards Chemin aux Boeufs.

Activity at the circuit went on for around 90 days of the year back in 1970. By the end of the 1990s, it reached 330 days per annum easily and today it is one of the busiest circuits in Europe. Aside from the Grand Prix, the Bugatti layout currently hosts the French Superbikes, its own 24 Hour races for bikes and trucks, a VW festival and the V de V Endurance Series.

Maison Blanche Circuit

With the Bugatti circuit becoming increasingly busy, in 1976 a second permanent course opened to provide an additional venue for testing and a home for a race school. Known as the Maison Blanche course, it is situated alongside the main course between the final of the Porsche Curves and the Ford Chicane. As it has never been used for racing events (nor was it designed to be) it is the oft-forgotten course by the wider world, despite being regularly glimpsed in coverage of the 24 Hours.

With multiple layout various possible and sharing a small part of its more famous big brother, the Maison Blanche course saw lots of use throughout the 1980s and '90s, with the race school and track day events proving popular.

In 2007 the course was completely redesigned, to bring it up to modern safety standards and also incorporate more of the main circuit. The longest layout variation now enters the 24 Hour circuit just ahead of the Virage Corvette, which now means it also takes in (appropriately) Maison Blanche corner itself.

In 2011 the circuit became home to France's only Porsche Sport Driving School and in 2015 a new Porsche Experience Centre opened on the site, with a new reception centre and servicing facilities added giving a unique experience for all Porsche fans and owners.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

- Automobile Club de l'Ouest, Circuit des 24 Heures, 72019 Le Mans, Cedex 2, France

- +33 2 43 40 24 24

- Email the circuit

- Official website

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 6512

Plan a visit

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.