Calder Park

Circuit Overview

Calder Park began with humble beginnings as a dirt track built by enthusiasts before growing into a behemoth paved road and oval complex, which consumed money at a faster rate than the cars going round it.

Sadly, it proved too ambitious a dream, leading to family rifts, a change in ownership and a reduced programme of activity, limited to mainly sprints and drag racing.

Today it makes a rather sad sight, as the Thunderdome sits effectively abandoned and the main circuit and drag strip sit similarly inactive, having yet to restart operations following the Covid-19 pandemic.

Circuit History

Located at Keilor, in the north east suburbs of Melbourne, the track began in the 1950s with a pair of motoring enthusiasts who wanted somewhere to race their FJ Holdens, Pat Hawthorn and Jim Houlahan. Hawthorn persuaded Houlahan to abandon plans for a wrecking yard and instead build a circuit on his newly purchased property at Digger's Creek. A dirt track was laid down and events soon began to gather pace.

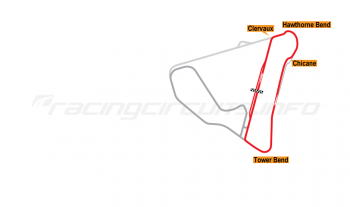

By 1962, the dirt had turned to asphalt when the track was paved, roughly to the same layout of the current Club Circuit. The inaugural meeting on the bitumen track was run by the Australian Motor Sports Club and took place on January 14, 1962. Competitors included a young Bob Jane in the number 84 Jaguar, Norm Beechey in the number 40 Holden and Peter Manton in a Mini Cooper S.

Despite initial promise under the AMSC, Calder Park failed to make money and a decision was taken to promote the facility on a more business-like footing. Wealthy businessman Jim Pascoe, who had helped finance the circuit, took over as manager and things soon began to accelerate in the right direction.

Under Pascoe's stewardship, Calder Park began to flourish, turning it from a tiny club racing venue into the most important permanent facility in Victoria by the end of the 1960s. Continuous development brought improved facilities and enhanced prestige. By 1969, the circuit had staged its first of 25 Australian Touring Car Rounds, with local racer Bob Jane taking the spoils in his Ford Mustang.

Bob Jane arrives

Then, just as it had hit new heights, tragedy struck with the sudden death of Jim Pascoe in May 1969. After a few years where the momentum seemed to stall, in stepped Jane who, as well as being a successful racer, had built up a large fortune thanks to his eponymous tyre retail business. In 1974 he purchased Calder Park, moved in next door into a property at Digger's Creek and set about transforming its fortunes even further.

Under Jane's tutelage, the circuit received ever more improvements, with grandstands and earth spectator mounds with good views of the action added to greet the ever-increasing crowds and a series of new events designed to draw them in further. The circuit not only hosted road racing but also drag racing, while the infield formed part of the rallycross track.

In 1980, Jane hit upon the idea of hosting the Australian Grand Prix to capitalise on the success of F1 World Champion Alan Jones, albeit as a non-championship invitational event. There were only two actual F1 cars - Jones in his familiar Williams and an out-of-date Alfa Romeo for Bruno Giacomelli. Local F2 cars made up the rest of the field; predictably, Jones won easily and the race was televised across Australia.

Jane thought better of the F1 cars the following year, the race being run instead for Formula Pacific cars, with F1 stars drafted in to drive against local stars. Over the next four years winners were Roberto Moreno (three times) and Alain Prost, against fields including the likes of Nelson Piquet, previous winner Jones, Keke Rosberg, Jaques Laffite, Andrea de Cesaris and Francois Hesnault.

First circuit changes

In 1982 the circuit was renamed to the Melbourne International Raceway, while 1984 saw the introduction of the first significant track changes in the circuit's history, with the insertion of new 'esses' at the former Lucas Loops section, and a re-profiling of the preceding corner to provide more run-off. The old pit lane on the infield and the timing and scoring tower were torn down, in favour of a much bigger pit lane on the outside of the main straight, with easy access to the paddock. Track distance remained at an official one mile, despite the changes.

Calder changed its name briefly once again in 1985 - no doubt at the whim of some marketing plan by Jane - to the grander sounding Keilor International Raceway. Signage was altered on the grandstands and elsewhere, though little else changed. By the following year, Calder Park was back in vogue once again as events came full circle.

The mid-eighties saw the biggest expansion of all at Calder, as Jane began to pursue his ambitions to bring new forms of racing the fore. While the brief dalliance with the world of Formula One at the beginning of the decade would not ultimately yield a World Championship event (the course was too small in any case), it did prove that Jane knew how to put on a show.

Grand plans and oval racing

It was perhaps not surprising therefore that he would go on to form an alliance with the France family, grandees of NASCAR, to bring American-style stockcar racing to prominence in Australia. As far back as the 1960s, Jane had visited America, touring venues such as Daytona and Charlotte to gauge the popularity of NASCAR racing. Into the 1980s, with Channel 7's Mike Raymond pioneering coverage of the US stockcars for Australian television, the time was ripe for a deal to be struck.

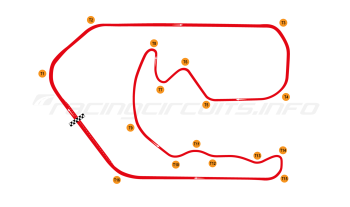

In 1981 Jane put pen to a contract with Bill France Jr., the head of NASCAR, to bring stock car racing to Australia and plans were laid out for a high banked oval adjacent to the existing Calder Park Raceway. This would be modelled after Charlotte in a scaled-down form with four turns and a dog-leg front stretch. Known as the Thunderdome, it was designed to be fast, with 24° banking on Turns 1, 2, 3 and 4, the front stretch at 4° and the back straight at 6°.

Ground first broke for the track in 1983 and it took four years to complete. It was built at a cost of A$54 million— with Jane personally contributing over $20 million of his own money. Specialist engineers were flown over from the USA to advise on the creation of the course, while huge amounts of earth were brought into the otherwise flat site in order to shore up the banking.

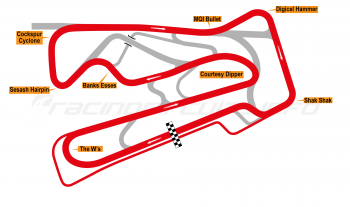

The plans also called for an extended road course which could be linked to the Thunderdome to create a combined 2.57 miles 'Grand Prix' circuit. This involved bypassing the Repco corner and extending the main straight from 700 metres to just under 1 km in length. A new switchback corner lead to a new right left corner complex, then up and down an artificial hill before rejoining the old course via a fast chicane. The final turn (which was known for a long time as Gloweave Corner) was also moved forward approximately 75 metres so that the road course and the start of the drag racing strip were separate, though the old corner remained for use as the pit lane entry.

The Thunderdome is ready

The newly extended road course (now known as the National Circuit) opened for business in 1986, while the finishing touches were being put on the Thunderdome. This duly opened for business the following year, with an official ceremony by the Mayor of the Keilor City Council on 3 August 1987.

The first race to enter the Thunderdome in anger was a 300-kilometre race for Group A touring cars, using a combined road and oval course. It was won by Terry Sheil and John Bowe in a Nissan Skyline, the only time a Japanese marque would head to victory at Calder. This event was soon followed on October 11 by the visit of World Touring Car Championship, as part of its Australian double header in the wake of the Bathurst 1000.

Dreadful weather conditions greeted the cars on race day, with heavy rains making the racing surface treacherous, particularly on the link road to the Thunderdome. Steve Soper and Pierre Dieudonné benefitted from the chaos to lead into the first corner in their Eggenberger Ford Sierra RS500 and never looked back. Only 16 cars were running by the time the race was flagged in drying conditions, with the Schnitzer BMW of Emmanuele Pirro and Roberto Ravaglia coming home in second. Much like the original WTCC, the event proved a one-off.

Also in 1987, the combined road-oval circuit was used for a round of the Swann Series for Superbikes. For safety reasons the bikes were not allowed onto the 24° banked turns in the Thunderdome and they had to use the flat track apron as the turns. The bikes were allowed onto the 4° front straight with cones placed around the perimeter to mark where the edge of the track was. It was an experiment which was not repeated; indeed, the combined circuit would see no further racing activity beyond 1987.

The first full oval race on the Thunderdome took place in January 1988 and was also the debut for the local AUSCAR series, featuring home built Holdens. As these were all right-hand drive as per local road regulations, the race was held in a clockwise direction, the opposite way to the usual norm for oval racing. There was another shock in store when 18-year-old female driver Terri Sawyer won the 110 lap race, beating the proprieter's nephew Kim Jane to the line in a Holden VK Commodore.

The NASCAR stars arrive

This event was followed a week later when the cars from the NASCAR Winston West series joined locals in the first NASCAR-sanctioned event outside of the US. In a test session prior the meeting, Richard Petty set an unofficial lap record for the Thunderdome of 28.2 seconds for an average speed of 142.85 mph. 'The King' didn't actually take part in the race itself, though his son Kyle represented the family name alongside other NASCAR luminaries such as Bobby Allison, Neil Bonnett, Michael Waltrip and Dave Marcis. Allan Grice, Dick Johnson and Kiwi racing legend Jim Richards provided some of the big name local interest.

Bonnett and Allison dominated the race, swapping the lead many times in the heat of the summer afternoon where cabin temperatures were reported to reach over 57° Celsius (135° Fahrenheit). Grice initially challenged up front until contact with Allison sent him spinning to the infield. During his charge back through the field he got caught up in the race's biggest accident, a multi-car crash on lap 80 in turns 3 and 4 involving 8 cars. With fading brakes, Grice ploughed into the stricken Ford Thunderbird of Dick Johnson, writing off both cars and sending Grice to the hospital with a broken collarbone.

Through the carnage, the American visitors reigned supreme, with Bonnett winning from Allison and Marcis as the NASCAR regulars filled the top 10 positions. Televised live in both Australia and the USA, the event proved a hit with both punters and drivers, so much so that many of the US contingent returned that December for the Christmas 500, which also featured Indycar legend Johnny Rutherford.

The arrival of NASCAR came at the right time to exploit a dissatisfaction within Australian race fans, who were weary of the domination of overseas brands in touring car racing. Crowds were initially promising, although they faded until the installation of lights at the Thunderdome for night racing in 1991 brought them back to peak levels. For the next five years the series enjoyed success, although with only one super speedway and few other circuits to race on, development of the series to a national audience was limited.

In 1992 Jane and Mike Raymond announced plans to turn the old ½ mile Harness racing track that surrounded the Parramatta Speedway in Sydney into a paved oval for NASCAR and the Australian AUSCAR category, giving Australia a third paved oval speedway. Unfortunately however the project never got past the planning stage, and Jane missed the chance to make stock cars Australia's premier form of motor sport.

Stockcars fade as V8s return

In fact, the Australian Touring Cars returned to Calder in 1996 after a gap of seven years and the circuit would re-establish itself as a mainstay for the category into the V8 Supercars era (including an infamous barrel roll for Craig Lowndes at the start of the 1999 event). As V8 Supercars began to re-establish their dominance on the Australian sporting landscape, so the the brief love affair with NASCAR dwindled. The NASCAR series never made it past 1999 and its AUSCAR second tier was on life support by 2001 and would disappear at season's end, never to return. The Thunderdome would fall silent to racing thereafter.

V8 Supercars, meanwhile, were increasingly turning to street races which it would promote itself and Calder Park didn't fit the mould and would also disappear after 2001. Thereafter a spat with the Confederation of Australian Motor Sport (CAMS) saw Calder Park lose its track licence. Though Jane was able to continue under his own auspices and host grassroots motorsport successfully and the licence was eventually restored in 2012, it did mean that top-level series stayed away (and, indeed, never returned).

There were a few attempts to revive interest in NASCAR racing, assisted mostly by the profile of former dual V8 Supercar champion Marcos Ambrose who raced in the NASCAR Sprint Cup in the United States, but the continued unavailability and general deterioration of the Thunderdome killed such plans before they started.

Family feud gets ugly

Worse was to come when financial worries reared their head at Bob Jane's companies, with the suggestion that the T-Marts business had been propping up the racing circuits (Calder Park and Adelaide International) for numerous years, a situation which had become untenable. Bob's son Rodney, himself a racer, was tasked with turning around the business, in return gaining full ownership of the company his father had founded. This would eventually lead to a family feud when Jane Jr realised that the profligacy towards the tracks would have to end. A hugely acrimonious legal case would cement the bad blood between father and son and when the courts sided with the younger Jane, things came to a head.

In December 2012 Bob Jane was removed from Calder Park Raceway by security guards after the take-over of the circuit by his son Rodney. Further court cases went back and forth, with Bob losing each time and further financial woes put him into bankruptcy. He continued to live on a plot of land at Diggers Rest close to the circuit he masterminded for several years, until even this was sold from under him by the authorities to go towards an unpaid tax bill. He died in 2018, estranged from his son and the businesses he founded, in what was a very sad end to proceedings.

Uncertain future

Today both Calder Park and Adelaide International Raceway are operated by the Australian Motorsport Club Limited, which had focused on drift events and drag racing, alongside promotional days, general testing and a very limited programme of club motorsport meetings. The Thunderdome sits almost in splendid isolation, decaying ever faster as the years pass by, while the road course is in serviceable, if not great condition.

Off street racing events were held on the drag strip until the end of 2019 and remained relatively popular. Indeed, there was some much-needed investment programmed for 2020, when the track was due to be resurfaced, forcing the regular drag meets to be put on hold. However, with the advent of the Covid-19 pandemic all of these plans were put into disarray and the regular meetings have yet to recommence. There is some light at the end of the tunnel however. While the planned Australian Nationals drag meeting in February 2022 has been switched elsewhere, pending completion of the resurface ANDRA says Calder should be back as host in 2023.

It seems likely that the once multi-use complex will continue to focus on hosting drag racing, with a continuing block on any racing activity. It's a very disappointing end to what should have been among the more exciting chapters in Australian motorsport history. Perhaps Bob Jane was too ahead of his time and over-ambitious; certainly the amount of money required to build and renovate the circuit over the years was way above anything that could be recouped from sponsorship or gate receipts. It was estimated by a Calder Park internal corporate memo to have cost A$250 million - a truly staggering amount of outlay, even supposing some of this could have been recouped.

Calder Park's future therefore seems somewhat in limbo. The land it sits on has little value for other uses as it sits under the flightpath of Melbourne's international airport and is criss-crossed by powerlines. In any case, the amount of earth moving required to build anything else on the site would likely rule out its viability for development purposes. So, unless another willing millionaire wants to lavish further funding on the place, Calder Park looks set to see out its days with relative modesty.

Jump onboard

Circuit info

- Calder Park Raceway, Calder Park, VIC 3037, Australia

Rate This Circuit

Votes: 1557

Plan a visit

Get your race tickets!

Brought to you with:

We've teamed up with Motorsports Tickets to bring you the best deals for Formula One, MotoGP, Le Mans and more.